Ketamine has been around for decades but only in recent years has it found applications in mental health. Ketamine treatments are available in two main frameworks, either with a course of psychotherapy or as a standalone medication. Read this guide to learn more about how ketamine treatment works and how it is used in therapy.

What is Ketamine?

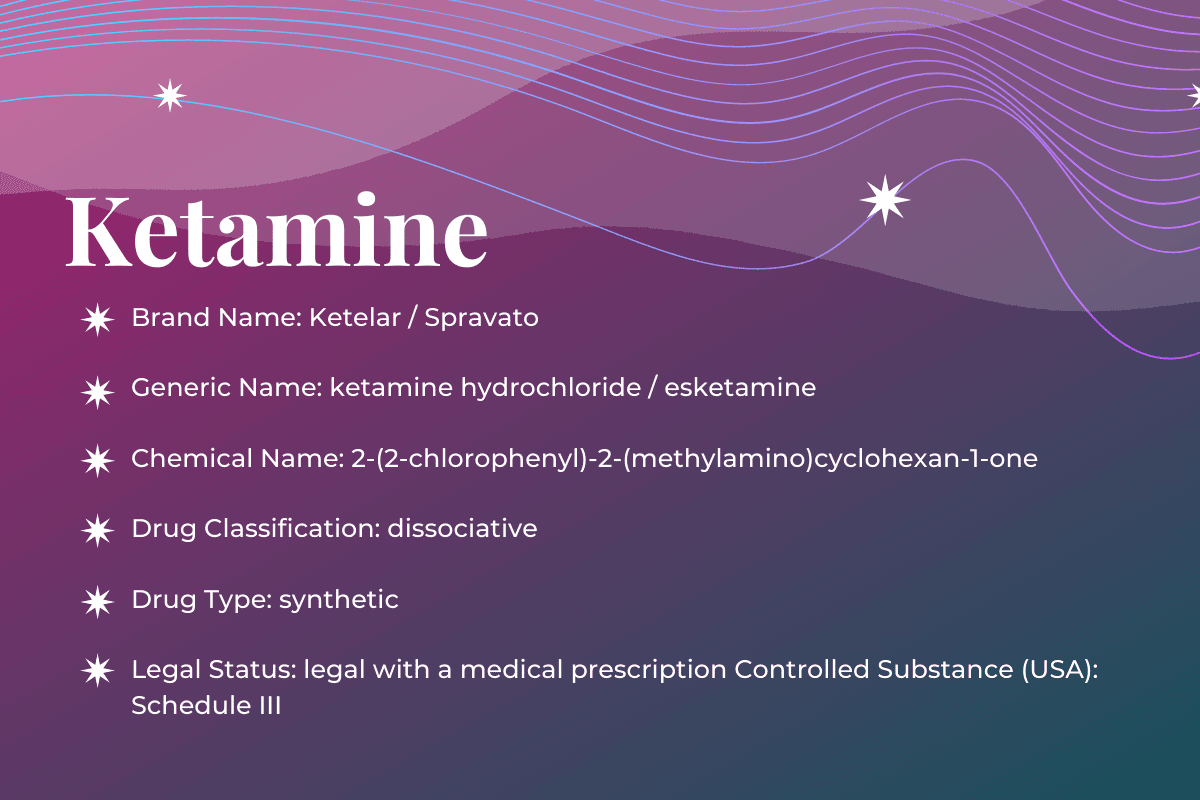

Discovered in 1962 and patented in 1963, racemic ketamine is an arylcyclohexylamine used as a rapid-acting general anesthetic agent in human and veterinary medicine. Following FDA approval in 1970 as an anesthetic drug, ketamine is now legally prescribed off-label for a growing list of indications.

Ketamine is a non-competitive NMDA antagonist and interacts with a number of other receptor targets that contribute to its effects. Beyond its primary application for anesthesia, it is used as an analgesic, anti-obsessional, and antidepressant compound, and may possess neuroprotective and neuroplastic properties.

The effects of ketamine are highly dependent on the bioavailable dose by way of the route of administration, ranging from slight perceptual disruptions to paralysis and full dissociation to sedation. In medical settings, ketamine is considered relatively safe because it has less circulatory and respiratory depression compared to other anesthetic agents. Long-term use and high doses of ketamine are associated with greater incidence of adverse effects and increased risk of dependence.

From the Streets to Psychotherapy Offices

What is ketamine treatment originally for? Ketamine is an anesthetic. It was discovered in 1962. However, since then, ketamine has been on an odd journey. Due to this, ketamine is widely misunderstood. Here’s why.

There are 2 main ways the vast majority of Americans have come to know ketamine.

Hearing it referred to as “horse tranquilizer.” And/or, hearing it referred to as its slang name among the electronic dance music and rave scene – “Special K”.

The mass media sensationalized these two soundbites over recent decades in order to bypass a nuanced conversation while pandering to the status quo’s anti-drug hysteria.

Although, to be fair, both of these misrepresentations have a bit of truth to them.

After its discovery, ketamine was later used widely in the Vietnam war, thanks to its pain killing effects that don’t inhibit respiratory functioning like other anesthetics. Ketamine can be preferable to other drugs and treatments due to its lower physically addictive quality. A dose used in this way induces a dissociative state providing pain relief, sedation and amnesia.

Over the years, ketamine was also used for anesthesia in animals. Unfortunately the mass media exploited a possible urban legend that quantities of ketamine were being stolen from veterinary clinics. Since it was used as a horse tranquilizer at veterinary clinics, the mass media latched onto this. The mass media made ketamine bigger, scarier and spookier. In reality, ketamine has been used on a wide range of animals, besides just horses. For example ketamine is used with: elephants, camels, gorillas, pigs, sheep, goats, dogs, cats, rabbits, snakes, guinea pigs, birds, gerbils and mice.

So ketamine isn’t just a horse tranquilizer, it’s also a wide ranging mammal tranquilizer, and this includes humans as well. But what about “Special K”?

This made for another sensational headline to connect “stolen horse tranquilizer” to raves and electronic dance music festivals. Parents were stricken with fear of simply letting their kids go out at night, lest they end up being knocked out like a horse. Of course this type of dose is much too large for a human. However, when used at higher levels, ketamine becomes a powerful hallucinogen. At high doses of this type, ketamine’s dissociative state leads to visual and/or auditory hallucinations.

Ketamine has taken an odd journey from the battlefield, to raves, and now to depression and PTSD treatment. Despite the circuitous route, ketamine always maintained its medical usefulness. Thus ketamine never strayed far from further research and studies.

Even though ketamine was always approved for anesthetic use by the FDA, it wasn’t used for mental health treatments until recently. After many years of use as an anesthetic, human studies for other applications and treatments began in the 1990s. Some of these new territories of ketamine explored schizophrenia.

During the 1990s Yale researchers “…started giving ketamine to healthy individuals to produce transient symptoms of schizophrenia with the idea that they could then study these individuals.” Since ketamine mimics schizophrenia symptoms (known as psychotomimetic effects), the researchers could “…study their brain activity to gain a better understanding of the condition.” A few years later, ketamine had a serendipitous moment. It was unintentionally found to be successful in treating depression.

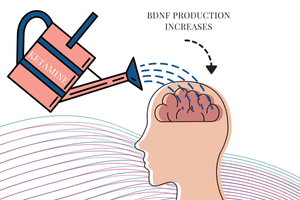

Discovering ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect led to an insight. Since ketamine works on a different neurotransmitter, compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it stimulates BDNF production. BDNF stands for brain derived neurotrophic factor. Some people think of BDNF like it’s Miracle Gro. Rupert McShane says “You can think of BDNF as a “fertilizer” for the brain.” McShane is an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford. He continues saying that BDNF boosts results in “…neurogenesis, the growth of new brain cells, and synaptogenesis, the formation of new connections between brain cells.” After that, ketamine never looked back.

What is Ketamine-Assisted Therapy (KAP)?

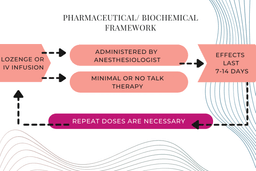

The use of ketamine for mental health symptoms falls into two broad frameworks – a pharmaceutical/biochemical framework and ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP). Ketamine itself has physiological effects that appear important for antidepressant and other therapeutic effects.

The pharmaceutical/biochemical framework has a neurobiological approach that often employs intravenous dosing by an anesthesiologist with no therapy. Some doctors will administer ketamine, typically through IV infusions or lozenges, to relieve psychiatric symptoms.

In this methodology, the drug itself acts through neurobiological mechanisms and the symptom relief is dependent on repeated administrations because the therapeutic effects last for days or up to two weeks. Patients are offered minimal support and no talk therapy which may lead to a dependence on ketamine to achieve symptom reduction. The contents of the experience or talking about interpersonal issues aren’t the focus of the treatment. Long-term use of ketamine is associated with negative side effects, namely kidney and bladder toxicity and ketamine tolerance and dependence.

Because symptom reductions usually only last for up to 7 days, repeated administrations of ketamine are necessary to achieve therapeutic benefits. If a patient takes ketamine long-term, they are at greater risk for negative side effects. These effects can be severe and cause toxicity to the bladder and kidney. Tolerance and dependence to ketamine can develop over time which can make medication cessation psychologically difficult.

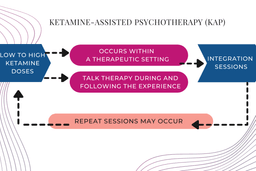

Ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is a method where low to moderate doses of ketamine are delivered with the intention of altering consciousness to facilitate psychotherapy. A therapist sits and talks with a client as they experience ketamines, and after the effects wear off.

Alternatively, KAP may also employ high doses of ketamine. High ketamine doses are used to induce a non-ordinary state of consciousness, provoking a person to experience major shifts of perceptions in many ways similar to classical psychedelics. Mystical-type experiences and feelings of ego dissolution are common for high dose sessions. These effects can be extremely negative if a person is not well prepared and supported during and afterwards.

Either immediately after the effects of ketamine dissipate, and/or in the days to weeks to follow, a person undergoes a course of counseling or psychotherapy to examine the experience and emotions within the framework of their personal goals. The psychotherapeutic process aims to stabilize positive behavioral changes, consolidate psychological material, resolve psychological issues, improve relationships, catalyze new insights, and enhance self-awareness.

While still under-researched, ketamine-assisted psychotherapy is presumed to amplify the neurobiological properties of ketamine by addressing underlying psychological issues and bolstering transformational healing.

For a robust explanation between the 3 ketamine therapy types (pharmaceutical/biochemical, low dose KAP, and high dose KAP) we strongly encourage you to follow the work of Dr. Raquel Bennett.

Raquel Bennett, PsyD is a psychologist and ketamine specialist from Berkeley, CA. She has been studying the therapeutic properties of ketamine since 2002. Dr. Bennett is the founder of KRIYA Institute and the organizer of KRIYA Conference, which is an international event devoted to the use of ketamine in psychiatry and psychotherapy. Dr. Bennett has a long-standing interest in the relationship between mood modulation and psychedelic experience.

Bennett has written much on the subject of ketamine, as well as the 3 different types of treatment methods over her 19 years of study. She sums up the subject best by saying:

So which of these treatment paradigms works the best? In other words, what is the “right” way to use ketamine therapeutically? The answer is that all of the paradigms are useful. In my 17 years of experience to date, it is clear that different things work well for different people: Some patients are excellent candidates for a series of low-dose ketamine infusions or nasal spray; some patients are tied up in emotional knots on the inside and truly benefit from ketamine-facilitated psychotherapy; and a tiny fraction of clinical patients are actually good candidates for a full psychedelic ketamine journey. Learning how to distinguish which patients are likely to benefit from each strategy is beyond the scope of this article and the subject of much active debate in the clinical ketamine community.

You can read the rest of Bennett’s essay here to learn more about these treatment methodologies and how to approach ketamine therapy.

Similar to other classical psychedelics, not everyone is the right fit for ketamine, especially at higher doses. Screening for contraindicated medical and mental health conditions is essential as is a proper setting for psychological safety. Research dating back to the 1950s and current day psychedelic-assisted clinical trials are elucidating how psychedelic experiences can be beneficial for therapeutic applications, and what parameters are necessary to support a person undergoing these experiences.

What Does Ketamine Do to My Brain (Pharmacology)?

PubChem describes the basic pharmacology of ketamine hydrochloride, by stating:

Although its mechanism of action is not well understood, ketamine appears to non-competitively block N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and may interact with opioid mu receptors and sigma receptors, thereby reducing pain perception, inducing sedation, and producing dissociative anesthesia.

This explanation concurs with why ketamine is often referred to as a “pharmacologist’s nightmare.” Ketamine has earned this nickname given its diverse array of effects at numerous receptors in preclinical research.

Indeed, there are (often conflicting) studies demonstrating effects on opioid, sigma, cholinergic, dopamine, serotonin, and adenosine systems, amongst others.

These additional properties aside, the best understood mechanism of action is via noncompetitive antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, first demonstrated in 1983.

NMDA receptors are ionotropic glutamate receptors found extensively in the central nervous system, and to a lesser extent peripherally. When NMDA receptors are activated by glutamate binding, ion channels are opened allowing for various positive charged ions to flow through them into cells, triggering membrane depolarization and modulating signal transmission. Ketamine blocks the flow of ions.

For a brief synopsis of ketamine’s pharmacological effects check out Drug Science’s resources or watch this video:

Ketamine Positive Effects

The subjective effects of ketamine are highly dependent on the dose administered. The environment where ketamine is taken, as well as the type of support or adjunctive therapies, strongly impact the drug effects and the subjective interpretations.

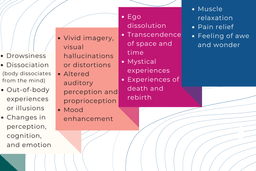

Here is a list of possible effects: drowsiness, dissociation (body dissociates from the mind), out-of-body experiences or illusions, changes in perception or cognition or emotion, vivid imagery, visual hallucinations or distortions, altered auditory perception and proprioception, mood enhancement, ego dissolution, transcendence of space and time, mystical experiences, experiences of death and rebirth, muscle relaxation, pain relief, feeling of awe and wonder.

Ketamine Negative Effects

Ketamine can also induce undesirable or negative effects. The risk for some of these effects are associated with the context where ketamine is taken. For example, unsupervised use of ketamine carries a greater risk of accidents, such as falling or car crashes. Prolonged use of ketamine is associated with different negative effects, often more severe, than the acute side effects.

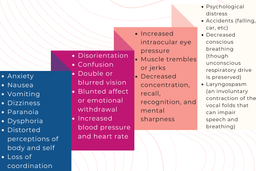

Here is a list of possible acute negative effects: anxiety, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, paranoia, dysphoria, distorted perceptions of body and self, loss of coordination, disorientation, confusion, double or blurred vision, blunted affect or emotional withdrawal, increased blood pressure and heart rate, increased intraocular eye pressure, muscle trembles or jerks, decreased concentration, recall, recognition, and mental sharpness, psychological distress, accidents (falling, car, etc), decreased conscious breathing (though unconscious respiratory drive is preserved), or laryngospasm (an involuntary contraction of the vocal folds that can impair speech and breathing.

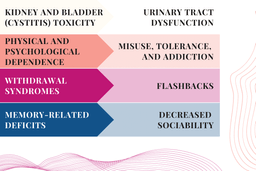

Here is a list of possible negative effects associated with prolonged use: kidney and bladder (cystitis) toxicity, urinary tract dysfunction, psychological dependence, misuse, tolerance, and addiction, psychological withdrawal syndromes, flashbacks, memory-related deficits, and decreased sociability.

In 2020, new safety information for chronic use was added to ketamine products marketed in Canada. Liver enzyme elevations, biliary ductal dilatations, and hepatic fibrosis were added to the section on warnings and adverse reactions.

Ketamine Contraindicated Medications and Conditions

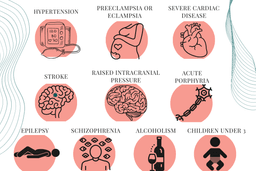

Several medical conditions are contraindicated for ketamine use or may increase the risk of side effects. Individuals with pre-existing conditions where elevated blood pressure would increase the risk for complications should avoid or be extremely cautious with ketamine.

Here is a list of contraindicated conditions: hypertension, preeclampsia or eclampsia, severe cardiac disease, stroke, raised intracranial pressure, acute porphyria, epilepsy, schizophrenia, alcoholism, and children under the age of 3. Patients with epilepsy are sometimes administered ketamine but with extra caution and medical oversight.

Unlike the classical psychedelics and MDMA, ketamine is considered safe and effective in combination with multiple classes of psychiatric and non-psychiatric medications. It is often given in addition to a wide range of antidepressants. However, medications that modulate glutamate and GABA may have strong influences, for example benzodiazepines and lamotrigine.

Ketamine History and Law

Ketamine’s discovery can be traced to phencyclidine (PCP). PCP was developed for anesthesia and was first tested on humans in 1958 under the name Sernyl. It was found to produce a “centrally mediated sensory deprivation syndrome” with a neural signature distinct from any other sedative or states like sleep.

Though PCP proved to be a potent anesthetic, a significant number of patients experienced “excitation” or “psychotic reactions” that could last for more than 12 hours after the anesthetic effects of a single dose wore off. These states went on to be referred to as “emergence reactions”, or delirium, and limited any further medical development.

Ketamine, originally called Cl-581, was synthesized as a derivative of PCP in 1962 in order to address this issue. Ketamine produced the same sort of “sensory deprivation syndrome” as PCP, but its development was pursued because it was metabolised much faster and therefore caused less “emergence reaction” as its effects wore off.

The scientists that synthesized ketamine initially proposed describing its unique effects as “dreaming”, in reference to the feelings of “floating” and markedly decreased sensation it induced. This term foreshadowed many of the future studies in anesthesia describing patient reports of vivid “ketamine dreams”, as well as the influential 2004 book “Ketamine: Dreams and realities” by Karl Jansen.

Instead, the term “dissociation” was selected as a more marketable descriptor of ketamine’s effects. This term was suggested by Antoinette Domino, the wife of the primary investigating chemist Ed Domino, based on his descriptions of how patients seemed to be disconnected from their surroundings. This term stuck and ketamine has largely been unknown as a “dissociative anesthetic”, at least in the realm of medicine.

Use in Medicine

Ketamine’s anesthetic properties differed dramatically from the existing anesthetic agents of the day — and still do. This novelty led to inappropriate early uses and suboptimal dosing regimens, which resulted in disruptive and distressing emergence reactions, poor quality sedation, and unpleasant hallucinations. Ketamine thus gained more initial interest as an anesthetic agent for animals, for which it is still used (earning its nickname as a “horse tranquilizer”).

In the late 1960s and 1970s, ketamine found a niche as a combat anesthetic in the Vietnam War, where it was prized for its potent anti-pain effects without risk of respiratory depression. It became the US’s most widely-used battlefield anesthetic and earned the name “Buddy Drug” in reference to its ease of use: many soldiers with little training or specialized equipment carried stocks of ketamine to administer to injured comrades.

From here, ketamine continued to attract interest in anesthesia, particularly in developing countries due to its unrivalled ease of use and for its safety. For this reason, it has been found on the WHO Essential Medicine list since 1985.

Further medical uses (with varying levels of evidence) include treating opioid-induced hyperalgesia, chronic pain, refractory status epilepticus, severe headache, and alcohol detoxification.

Appearance in Psychiatry

Most modern works trace ketamine’s use in psychiatry to the first randomized controlled trial in depression, published in the year 2000.

However, the first works describing the use of ketamine in psychiatry date to at least the early 1970s by authors in Mexico, Argentina, Iran, and the former Soviet Union. These works all posited psychological (or psychedelic) mechanisms of action, rather than purely biological effects. Much like other psychedelic treatments, and unlike almost all psychiatric medications, these early protocols featured time-limited treatments rather than long term regular dosing. Also like other psychedelics, ketamine was initially combined with a variety of diverse psychotherapeutic approaches, including a form of psychoanalysis incorporating shamanic elements and a therapy described as “death and rebirth”.

Notable other early works documenting psychedelic uses of ketamine include two books: John C Lilly’s memoir “The Scientist” and “Journeys Into the Bright World” by Marcia Moore and her husband. Both works were published in 1978 and described psychedelic experiences from self-experimentation with ketamine.

These early forays into psychedelic uses of ketamine were largely ignored by mainstream psychiatry. This reflects the general movement away from psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, as well as psychiatrists wanting to distance themselves from public figures like Marcia Moore, who died following self-experimentation with ketamine. Shortly after her book was published in 1978, she disappeared. Two years later, her body was found in the woods near her Washington home. It is believed that she self-administered ketamine alone and subsequently died of exposure.

These publications did, however, contribute to growing recreational use. Owing to such use, particularly low-doses as part of dance culture, ketamine was scheduled by the DEA in 1999 as a drug with significant abuse potential (but confirmed medical utility as a Schedule III compound).

Modern Uses of Ketamine Treatments in Psychiatry

As described above, the first appearance of the modern intravenous ketamine protocol was a small randomized controlled trial in the year 2000, which tested a 40-minute infusion of 0.5 mg ketamine per kg of body weight in 7 depressed patients in a double-blind fashion. A rapid, dramatic improvement in depressive symptoms was shown.

This experiment and its dosing was based on the authors’ years of research on the use of ketamine as a tool to model psychosis. In this framework, the subjective effects of ketamine are described as psychotomimetic — that is, mimics of psychosis — rather than psychedelic.

These promising results were confirmed by dozens of subsequent randomized controlled trials, reigniting interest in psychiatric uses of ketamine. In the past several years, public interest has also exploded, resulting in ketamine appearing on the cover of Time Magazine in 2017 as a breakthrough treatment of depression. Michael Pollan’s 2018 international bestseller “How to Change Your Mind” also largely reignited public interest in psychedelics.

Extensive investments in research and development also recently led to the first FDA approval for ketamine for a psychiatric indication in 2019 with the approval of an intranasal formulation of the s-enantiomer of ketamine, Spravato™. Spravato has been approved for treatment-resistant depression in conjunction with a regular oral antidepressant. As with the intravenous protocol, the psychoactive effects of Spavato™ are typically framed as unwanted treatment side-effects that mimic psychosis.

Research on the psychedelic use of ketamine has also continued throughout the United States and abroad, though at a much smaller scale than the biomedical research. As discussed later, this paradigm differs significantly from the biomedical body of research in several ways.

The psychoactive effects of ketamine are seen as potentially therapeutic, not treatment side effects.

Dosages and routes of administration, including subcutaneous injections and sublingual lozenges, differ significantly from the model of Spravato and typical intravenous ketamine protocols. They are typically tailored to individual patients to a much higher degree than the biomedical model.

The psychedelic model aims typically to create lasting change with brief treatment courses in conjunction with psychotherapy, rather than with long-term repeated dosing of ketamine.

For a thorough review of the history of ketamine, please watch this video:

Doctors are prescribing ketamine for the treatment of depression and other conditions. You can learn more from the Ketamine Advocacy Network and The Brain-Mind Institute of New England.

Psychotherapeutic Applications for Ketamine Treatment

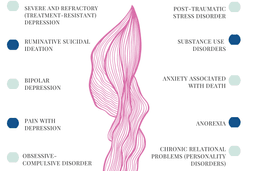

Ketamine has a wide variety of treatment possibilities that are being explored in scientific trials. Ketamine sees potential benefits in treatment for: severe and refractory (treatment-resistant) depression, bipolar depression, ruminative suicidal ideation, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), pain with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders (cocaine, opioids, alcohol), anxiety associated with death, anorexia, and chronic relational problems (personality disorders).

Ethical Guidelines for Ketamine Clinicians

Therapeutic use of ketamine has grown exponentially over recent years, thus creating a lot of gray areas in the mental health field. Dr. Bennett of the Kriya Institute has addressed the ethics of ketamine therapy and administration. We encourage you to read her thoughts here in, Ethical Guidelines for Ketamine Clinicians.

Clinical Trial Publications of Ketamine Therapeutic Use

Here’s a sampling of the most impactful findings from ketamine clinical trials.

Ketamine and Depression: A Review

A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders

Ketamine Psychedelic Therapy (KPT): A Review of the Results of Ten Years of Research

Ketamine as treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: a review

High-dose ketamine infusion for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans

Therapeutic infusions of ketamine: Do the psychoactive effects matter?

Experience of the use of Ketamine to manage opioid withdrawal in an addicted woman: a case report

Titrated Serial Ketamine Infusions Stop Outpatient Suicidality and Avert ER

Clinical Trials Now Enrolling Participants for Ketamine Treatment

Ketamine clinical trials might be some of the most common, psychedelic clinical trials found worldwide. As a result, there are too many to list here. However, we can point you in the right direction.

The best place to start is right here in our searchable trial directory. Clicking through will bring you to a compilation of 800+ ketamine studies around the world that are either recruiting, not yet recruiting, or completed.

Some clinical trial participants have volunteered to go public with their journey and talk about how ketamine-assisted psychotherapy helped them heal. The best way to learn about the potential of ketamine as medicine is the people who’ve used it to heal.

Ketamine Treatment Testimonials from Patients

- “Recently I have had to face a very painful and difficult life experience and since my ketamine session a week and a half ago, I have felt significant emotional relief. It’s as if my mind and heart simply can’t go back to that old painful place. As a psychologist, meditator, and healer myself, I am familiar with many healing ways and to help myself through this challenge I have tried, psychotherapy, shamanic work, the medicine of friendship, mindfulness, and more, and nothing has been nearly as helpful nor as potent as my ketamine session.”

- “I’m finally present for my family. I’m enjoying real quality time with them. Both at home and out on the town. It means everything to me to be with my family. Both physically & mentally. Especially when my ptsd often took me out of the room even if I was still there physically. In many cases I was just going through the motions. No longer.”

- “If you suffer from PTSD and want to feel like yourself again? If you can’t remember what normal reactions to triggers felt like? If you’re paralyzed in any aspect of your life? Going out? Being social? Relationships, friendships or work environments? I’m writing this review today to tell you that you CAN feel normal again. No matter how impossible that seems based on years of nothing working for you. I’m living proof that being at home in your own skin is possible again.”

- “It’s just been transformative,” Lynn told me. She calls Wolfson and Andries “miracle workers.” Michael is not, by his own admission, cured. He still has bad days, and he still needs occasional ketamine “booster” sessions to keep his mood up. But he credits ketamine with bringing him back to life and, ultimately, with saving his relationship with his wife. “It’s probably the only reason I’m still married,” he says.

- “It was indeed transformational,” Mathis said. “Nothing less than transformational.”

- Mathis described the experience as taking him out of his own ego, a “tilt(ing) of the prism on how I see things. It allowed me to have a detached, philosophical view on all things — me, my place in the world, my relationships.” This helps him make sense of his emotions “in a way that can be extremely difficult and sometimes even impossible to do when I am inside of myself,” referring to his default, day-to-day mental state.

- “First let me say that I have tried over 10 different SSRI/NDRI’s over the last 20+ years, talk therapy, cognitive therapy, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, wellness centers, etc. Nothing has helped me get my severe “treatment resistant” depression in check. NOTHING. I was so exhausted from trying something new and it not working. I had pretty much given up any hope that I’d be able to lead a “normal” life. Then a dear friend of mine told me that she had done ketamine infusion therapy and that it changed her life. She is in the same boat as me, except she also suffers from anxiety. I do not. I knew that this type of therapy was going to be expensive as insurance does not cover it. But I knew that it could be the most important investment I would make in my life. And it WAS. These infusions changed my life! They legit SAVED my life. I honestly had very little hope going into this, but I came out a changed person who got her life back. I now know what it feels like to live a normal life. I am super happy, the dark cloud that had been following me around is gone, the sky is bluer, the grass is greener and I have so much gratitude now. I have gone from a negative Nancy to a positive, grateful, blessed person. I was shocked at how quickly this treatment worked. It did take me until around my 4th infusion to finally feel the effects, so I extended my treatment by 3 more sessions. So glad I did. This has literally been the best thing I could have ever done for myself…”

Psychotherapy Testimonials from Therapists

So what do therapists have to say? The picture wouldn’t be complete without hearing from a therapist’s perspective, especially in regards to a not yet legal treatment.

- “Many clients find that ketamine experiences, delivered within a psychotherapeutic setting, foster greater insights into themselves and their interpersonal relationships, and enhance their overall sense of well-being.”- Polaris Co-Founders

- “Recent data suggest that ketamine, given intravenously, might be the most important breakthrough in antidepressant treatment in decades. First and most important, several studies demonstrate that ketamine reduces depression within six hours, with effects that are equal to or greater than the effects of six weeks of treatment with other antidepressant medications. Second, ketamine’s effects have been noted in people with treatment-resistant depression. This promises a new option for people with some of the most disabling and chronic forms of depression, whether classified as major depressive disorder or bipolar depression. Third, it appears that one of the earliest effects of the drug is a profound reduction in suicidal thoughts.”- Tom Insel, MD, former Provost of Harvard University and former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health

Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy Training Opportunities

Want to get more familiar with ketamine, and ketamine psychotherapy? We’re offering our FREE “Little Book of Psychedelic Substances” that includes ketamine and esketamine information. The book also includes a wide array of other psychedelics currently being vetted for psychotherapeutic use.

Ketamine therapy training for physicians as well as licensed mental health providers is essential for safe delivery of this powerful and potentially addictive substance; If you are a clinician and would like training to offer ketamine in your practice, or would like to learn more about the science and therapeutic approaches, take our 5-hour self-paced ketamine course (CE/CME available).