Drug Class

Ibogaine is an indole alkaloid found in several plants belonging to the Apocynaceae family, commonly known as the dogbane family. This family of flowering plants tends to be rich in alkaloids and cardiac glycosides. Ibogaine is a member of the tryptamine class similar to other psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD, and DMT.

What is Ibogaine?

Ibogaine is a naturally occurring psychoactive alkaloid found in iboga plants. The highest concentration of ibogaine occurs in the inner root bark of the West African shrub Tabernanthe iboga. Used in West Africa for thousands of years for religious and ritual purposes, iboga features prominently in the ceremonies of West Africa’s Bwiti people.

Beyond ceremonial use, ibogaine has attracted attention for disrupting addiction disorders and reducing withdrawal symptoms. Despite not being an approved medication in any country, many ibogaine clinics operate around the world. Researchers are interested in testing ibogaine in placebo-controlled studies to learn more about its safety and efficacy.

However, negative cardiac effects associated with ibogaine can lead to death and over 30 cases have been reported in the literature. It’s imperative that any treatment facilitators have emergency cardiac equipment (an automated external defibrillator) on hand and for any participants to undergo a thorough cardiac evaluation prior to ingesting ibogaine.

Here is a short video that gives an overview of ibogaine:

Let’s explore this plant more, starting with its traditions and history!

History and Culture

The ethnobotanical use of the iboga plant in West Africa for sacred, healing, and ceremonial purposes goes back centuries. The most well-known use of iboga’s root bark for ceremonies occurs among the Bwiti centered in present day Gabon but spread across Cameroon, Congo, Zaire, and Equatorial Guinea. A monotheistic and universal religion, the ceremonies are considered open to all.

In the mythology of the Bwiti, iboga is the tree of knowledge of good and evil, as depicted in the myths of the old testament of the Bible. The Bwiti believe the plant helps them heal and communicate with their ancestors. In ceremonies, they can experience life after death, visions of their ancestors, and powerful insights into their lives. Ceremonies often include intense trans music, rituals, dances, and performances. Iboga is consumed at various doses. Large doses are used during rites of passage, and lower doses are often used as a stimulant for higher energy. In the regions of Gabon, Congo and Cameroon, people have used iboga to overcome fatigue, hunger, thirst, and to increase sexual libido.

In the Western societies, ibogaine was first discovered by the French and Belgians who experienced the African iboga ceremonies. The earliest publication was made in 1864 by ethnobotanist Griffon du Bellay after he brought a sample of iboga to the West. In 1885, Father Joseph-Henri Baillon classified the plant and described its religious and ceremonial use. In 1901, ibogaine was isolated by scientists and by the 1930s, was being marketed as a stimulant in France.

Then in 1962, Howard Lotsof, a New Yorker with a daily heroin dependency, was involved with a group of people studying different psychoactive substances. A chemist friend provided a sample of ibogaine and after a 20 hour psychoactive experience, he realized that he hadn’t taken heroin for a day and half – but he felt no withdrawal symptoms. His mindset towards heroin changed as well and he realized that it emulated death, so he decided to choose life. After his successful treatment, he shared what he learned among his friend group and created awareness among the public about the therapeutic use of ibogaine, calling it an “addiction disrupter”.

Underground psychedelic therapists began to hear about ibogaine thanks to the work of Lotsof and began using it in their treatments. Unfortunately, ibogaine got caught up in the drug panic of the ‘60s and was placed into the most restrictive Schedule 1 of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act. This led to a lull of interest in the ‘70s – though the famed psychotherapist Claudio Naranjo did file a patent on ibogaine’s use for psychotherapy in 1974 (as documented in his book ‘The Healing Journey’).

In the early ‘80s, the increase in the use of heroin, cocaine, and crack led to a renewed interest in ibogaine for addiction treatment. Lotsof made an ally marijuana legalization activist and Yippie member Dana Beal. With Lotsof’s wife Nancy, they founded the Staten Island Project to secretly give ibogaine treatments to those in need. Lotsof formed a non-profit corporation to patent ibogaine and started petitioning the National Institute of Drug Abuse. But he was met with indifference and skepticism. The NIDA researcher Dr. Doris Clouet took an interest – but she eventually lost her job over it. No pharmaceutical companies displayed any interest either.

The first International Conference on Ibogaine met in 1987 to bring together researchers and advocates. The first human experiments began in Holland at the same time as Dr. Stanley Glick showed that ibogaine could reduce morphine self-administration in rats. ACT UP formed to fight the AIDS crisis and Dana Beal included ibogaine to their movement of harm reduction. The Black Panthers began to adopt the ibogaine cause in their quest for community medicine.

In 1991, Lotsof met with Dr. Debora Mash of the University of Miami. Using her political clout, she received FDA permission for a human clinical study – but not from NIDA. They threw up as many roadblocks as possible to research ibogaine and required more animal toxicity studies. Meanwhile, a study emerged out of Holland showing a 40% efficacy rate.

However, a study came out from Dr. Mark Molliner showing that ibogaine caused neurotoxicity in rats. He used dosages 5 times higher than those used in addiction treatment – but the media seized on it. NIDA held a meeting in 1994 with ibogaine experts and all agreed that it is not neurotoxic (even Dr. Molliner) and that safety evidence was sufficient for a Phase 1 clinical trial. But the conservative associate director of NIDA Dr. Frank Vocci brought in outside experts who said that no treatment can break addiction. Vocci then halted all trials, even the preclinical animal work, and no public funds would again be used for ibogaine research.

The medical use instead switched to underground treatments in the United States and unregulated treatments in places like Costa Rica, Mexico, and New Zealand (two observational studies have emerged from the latter countries). A review of the clinical studies can be seen here. In 2021, Phase 1/2a clinical trial for opioid withdrawal was approved by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). More clinical trials are being planned including one by ICEERS.

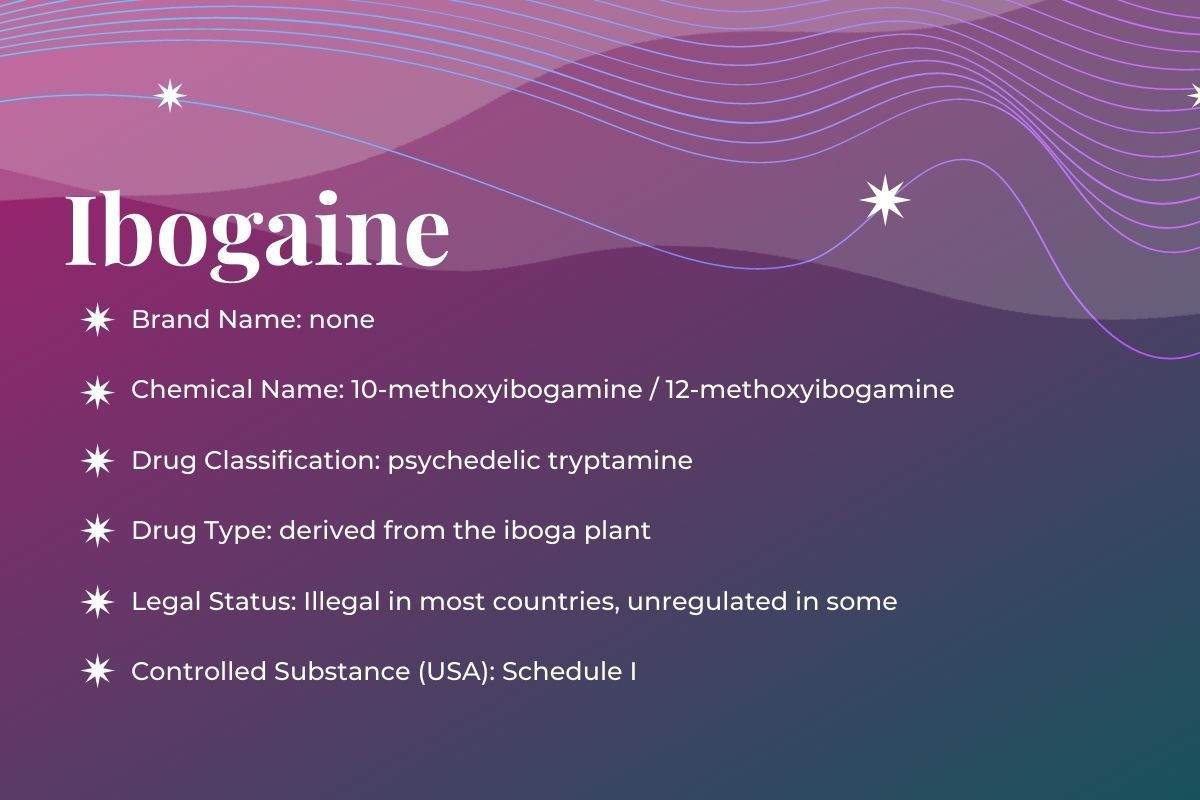

Legal Status

Currently, ibogaine is a Schedule I substance in the United States and is illegal in most of Europe, including France, Norway, Finland, Italy, Belgium, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Some countries decriminalized ibogaine only for medical reasons, such as New Zealand. Other countries have unregulated laws for ibogaine. The substance is legal to possess in Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Gabon, and Costa Rica. Even with current regulations, many treatment centers exist in Mexico, Europe, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Now there are many ibogaine centers and underground practitioners offering ibogaine for addiction treatment.

Pharmacology: What Does Ibogaine Do to My Brain?

While poorly understood, we do know that ibogaine interacts with a host of receptors in the brain, including opioid, sigma, glutamate, and nicotinic receptors. Due to this complex nature of the substance, it is still not entirely known how ibogaine mediates its therapeutic effects.

When ingested, ibogaine is rapidly metabolized by the liver into noribogaine. This chemical acts as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor to increase synaptic levels of serotonin and m-opioid receptor agonist. It also modulates the dopamine and glutamate systems.

Ibogaine can help lessen the withdrawal effects of opioids by blocking the receptors responsible for opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms. These effects are unique compared to classical psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin.

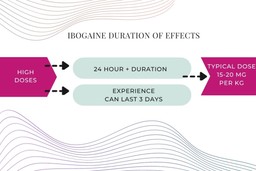

Beyond anti-addictive properties, ibogaine also induces powerful psychedelic experiences. The duration of effects last much longer than the classical psychedelics. With a heavy dose, it can last as long as three days, it typically causes a 24+ hour experience. The typical dose of ibogaine for a psychedelic effect is 15-20 mg per kg.

Research has found several receptors that ibogaine binds to and acts upon:

- Serotonin receptors

Like other psychedelic drugs, ibogaine inhibits serotonin reuptake in the brain. This leads to greater amounts of serotonin for binding to the serotonin receptors.

- Dopamine receptors

Ibogaine can inhibit dopamine release in the brain areas relevant to addiction. Ibogaine is beneficial for modulating BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), a signaling molecule crucial for neuroplasticity, memory, neuroprotection, and neural growth.

- NMDA-glutamatergic receptor

Ibogaine blocks the activity of the NMDA receptor. The activity of ibogaine on NMDA receptors is suggested as a possible mechanism for its non-addictive properties.

- Opioid receptors

Noribogaine acts as a m-opioid receptor agonist and k-opioid receptor partial agonist. It can also modulate a protein called GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor), which plays a significant role in the health of our brain receptors.

- Sigma-2 receptor

Ibogaine has a high affinity for sigma two receptors, and this may be related to mediating its neurotoxicity.

6. Noribogaine

This metabolite of ibogaine produced by the liver can stay in the system for several days. While not able to treat opioid addiction on its own, it seems to work synergistically with ibogaine to lessen withdrawals. Ibogaine and noribogaine have distinct pharmacologies.

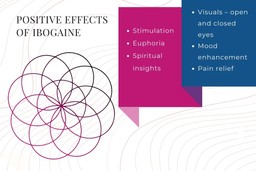

Positive Effects

The positive effects of ibogaine are similar to other psychedelic drugs, but the psychedelic experience can be more intense with greater discomfort. The effects are quite dose-dependent and highly influenced by the factors such as set, setting, and the user’s intention.

The positive effects of ibogaine include:

- Stimulation

- Euphoria

- Spiritual insights

- Visuals – open and closed eyes

- Mood enhancement

- Pain relief

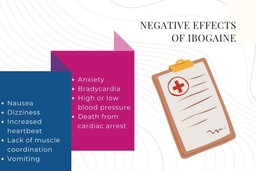

Negative Effects

There are also adverse effects of ibogaine that can create discomfort during the experience.

Some of the adverse effects include:

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Increased heartbeat

- Lack of muscle coordination

- Vomiting

- Anxiety

- Bradycardia

- High or low blood pressure

- Death from cardiac arrest

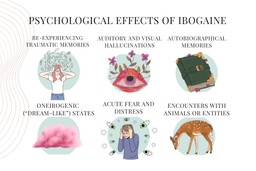

Psychological and Emotional Effects

Ibogaine is a powerful psychedelic with a high degree of intensity. Some of the psychological effects of ibogaine include:

- Re-experiencing traumatic memories

- Auditory and visual hallucinations

- Autobiographical memories

- Oneirogenic (“dream-like”) states

- Acute fear and distress

- Encounters with animals or entities

In 2019, Dr Thomas K. Brown and his colleagues conducted a study exploring the subjective effects and transformative states in treating opioid use disorder.

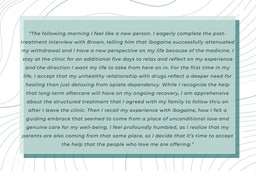

A person in this study who underwent the treatment reported:

“Ibogaine fundamentally changed something within me, I had done detoxes before but always gone back. After ibogaine, I had absolutely no desire to use drugs.”

Another individual explained their experience as follows:

“Most intently, I recall feelings of remorse, sorrow, and grief. And loss—hopelessness that I could never have back all the love that I threw away.”

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.Ibogaine Contraindicated Medications and Conditions

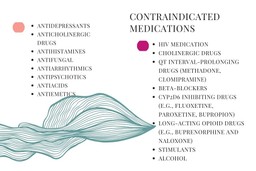

Ibogaine has several risk factors that one should consider before and after the experience. Serious adverse effects of ibogaine often stem from cardiovascular stimulation and according to MAPS, over 30 people have been reported to die in the scientific literature. Individuals who have undiagnosed or diagnosed cardiac conditions can experience severe adverse effects including death. Adverse effects can even show up the following days, so it is vital to have screening before and oversight after the treatment. Cardiotoxicity is a major risk for ibogaine. Therefore, proper screening including an ECG/EKG to evaluate heart health and medical supervision is critical for ibogaine use.

Many medications can have dangerous interactions with ibogaine. The list includes heart, psychiatric and long-acting opioid medications. The liver enzyme CYP2D6 is responsible for the metabolization of ibogaine to noribogaine. Some medications can interfere with this enzyme and result in adverse drug interactions. For this reason, drugs inhibiting CYP2D6 liver enzymes can be dangerous to mix with ibogaine. Also, medications that increase the heart QT interval must be ovoided.

Drugs that potentially interact with ibogaine, block the CYP4502D6 enzyme, or prolong the QT interval must be avoided. For example:

- Antidepressants

- Anticholinergic drugs

- Antihistamines

- Antifungal

- Antiarrhythmics

- Antipsychotics

- Antiacids

- Antiemetics

- HIV medication

- Cholinergic drugs

- QT interval-prolonging drugs (methadone, clomipramine)

- Beta-blockers

- CYP2D6 inhibiting drugs (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine, bupropion)

- Long-acting opioid drugs (e.g., buprenorphine and naloxone)

- Stimulants

- Alcohol

Moreover, ibogaine can trigger underlying mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia, bipolar, and psychosis. If someone has been hospitalized due to mental health condition, it is recommended to do a psychological screening before getting an ibogaine treatment.

Due to high risks and contraindicated medications, it is recommended to use ibogaine under the supervision of a medical doctor. Aftercare is also consequential after the ibogaine session. Let’s explore the psychotherapeutic applications of ibogaine and the treatment centers that offer ibogaine-assisted therapy.

Psychotherapeutic Applications of Ibogaine

Though not tested in placebo-controlled trials, many people in observational and open-label studies report ibogaine to be helpful in reducing withdrawal symptoms and lowering their desire to use other drugs. Research has found lower doses of ibogaine (10-12 mg/kg) can drastically decrease withdrawal effects and craving in heroin, cocaine, and opiate addicts. Long-term recovery can be achieved with one to three sessions but the treatment doesn’t work for everyone.

In 2014, a study in Brazil was conducted on 75 previous alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine users who had ibogaine treatment. 61% of patients remained sober one year later. The researchers further reported:

“Despite the limitations of the present report outlined above, the present data are the first formal clinical report to our knowledge that suggests that ibogaine has a strong therapeutic potential in the treatment of dependence on stimulants and other non-opiate drugs and that the medical complications previously reported can be avoided by administering the compound in the presence of a physician in a safe and legal medical setting.”

A former drug user Kevin Franciotti who participated in a MAPS-sponsored observational study of ibogaine treatment for opiate dependence describes his experience in this article. He mentions:

Even though the main emphasis seems to be ibogaine for the treatment of addiction, the substance is purportedly beneficial for many other things. Ibogaine referred to as the “stern father” of plant medicines can initiate meaningful experiences, which may help resolve past traumas and create a deeper awareness of mind, body, and experiences. Many people report increased introspection and reflection towards their relationships and life’s path.

Examples of Psychotherapeutic Experiences with Ibogaine

Here is a TEDx talk from Thomas Kingsley Brown where he explains how ibogaine can treat opioid addiction.

Joe Rogan talks about ibogaine for addiction treatment.

Here is a talk from Tobias Erny about microdosing iboga and ibogaine.

The founder of The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), Rick Doblin, PhD, shares his personal experience with ibogaine.

Here we witness an African ibogaine ritual from the perspective of journalist Hamilton Morris.

Researcher Paul Glue, MD gives a talk on ibogaine and its effects on opioid withdrawal.

Documentaries about Ibogaine

In this French-made documentary, Gilbert Kelner shows modern Bwiti use and the perspective of the Bongo people.

The ICEERS documentary is directed by Ben Deloenen and talks about a story of a heroin addict who gets treated with ibogaine in a clinic in Mexico.

Here is a TV series published on BBC where Bruce Parry undergoes an experience with Ibogaine.

A documentary by Michel Negroponte that follows Dimitri Mugianis on his journey with ibogaine that ended his heroin addiction and led him to Bwiti.

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.Ibogaine Treatment Centers

Many ibogaine treatment clinics exist in Mexico, Canada, South Africa, Costa Rica and Europe due to loose regulations on the substance.

Here is a video of a person who had ibogaine therapy. She talks about her healing experience in a treatment center in Mexico.

If you are looking for support before and after attending ibogaine retreats, the Psychedelic Support Network has experienced therapists to work with you.

Research and Clinical Trials

Even though the potential of ibogaine for addiction has been known for many decades, there have been no completed placebo-controlled clinical research trials.

Here’s a few of the best review articles:

2021: A narrative review of the pharmacological, cultural and psychological literature on ibogaine

2016: The antiaddictive effects of ibogaine: A systematic literature review of human studies

2009: Tabernanthe iboga : a Comprehensive Review

2001: Ibogaine: a review

Here’s the most important human and animal research:

2017: Treatment of opioid use disorder with ibogaine: detoxification and drug use outcomes

2017: Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study

2014: Treating drug dependence with the aid of ibogaine: a retrospective study

2001: Ibogaine in the treatment of heroin withdrawal

2000: Ibogaine: complex pharmacokinetics, concerns for safety, and preliminary efficacy measures

1999: Treatment of acute opioid withdrawal with ibogaine

1998: Observations on treatment with ibogaine

1994: A preliminary investigation of ibogaine: case reports and recommendations for further study

In this video, Thomas Kingsley Brown talks about the long-term outcomes from a study of ibogaine treatments in Mexico: