Our Roots

Early humans worshiped a great goddess. Thousands of archeological artifacts representing the Great Mother have been discovered across the globe [1]. In antiquity, reverence for the feminine was rooted in reverence for the earth and the powers of birth and death [2].

When human societies became more complex, a shift from egalitarian to patriarchal social organization took place. Greek culture and mythology overtook Goddess worshiping societies in Europe. The one unified Great Goddess was split into “partial goddesses” embodying her various aspects: fertility, love, wisdom, and even death [3].

As patriarchy progressed, Mother Earth was replaced with the Sky God, who was literally above the earth, beyond the body. The Sky God asserted a sense of control over the chaotic forces of nature and emotion [4].

In Psychedelic Spaces, We Give Ourselves Over to These Chaotic Forces

A psychedelic journey should not be taken lightly. Even small to moderate doses can bring to the surface unconscious material, including trauma memories and dissociated aspects of self. This can be overwhelming and disorienting if one is unprepared or unsupported. Higher doses can induce the experience of ego dissolution, where there is a loss of one’s sense of self.

Such experiences necessitate preparation, support, and integration, each of which may include mythological or spiritual frameworks. These frames can support meaning-making, provide containment, and serve to contextualize a confusing personal experience within a larger schema.

Hero’s Journey?

There is a lot of talk about “ego death” in the current Western psychedelic renaissance. Mystical experiences are hunted down, fetishized, and commodified, often at the expense of Indigenous sovereignty.

To date, discussions around the phenomenon of ego dissolution in psychedelic spaces have had a distinctly masculine tone. Terence McKenna coined the phrase “the heroic dose” to describe high-dose psychedelic trips aimed at “ego-dissolution.” But is the hero the most helpful metaphor?

The hero is one who conquers. Often he is conquering the forces of nature and the feminine, be they external or within his own being. The hero myth historically has glorified acts of violent conquest by an individual male over the earth and women. Heroes from Greek mythology to the days of Christopher Columbus were colonizers and rapists. Unfortunately, we see this type of ego-driven, patriarchal “hero” consciousness alive and well in the Western psychedelic realm today.

The Truth About the Dark Goddess

The Dark Goddess has gotten a bad rap over the years—as have goddesses, women, and all things categorized as feminine. The archetypal Dark Goddess is a profoundly caring energy. She guides us to the places in our own psyches we don’t want to go. She is the inner impulse toward the evolution of consciousness.

The mythology of the underworld, death, or dark goddesses offers a different perspective, value system, and psychological framework for holding and integrating psychedelic experiences individually and as a culture. The Dark Goddess “keeps the necessary balance, implacably sweeping away the old or what has gone too far” [5].

Ancient Goddess worship involved “entering into a process of self-transformation.” The archaic quest for oneness with the divine involved loosening the boundaries of the ego. This process threatened the burgeoning patriarchal consciousness built on such ego pursuits as domination and accumulation of resources [6].

As Above, so Below: Antidote to the Hero’s Quest

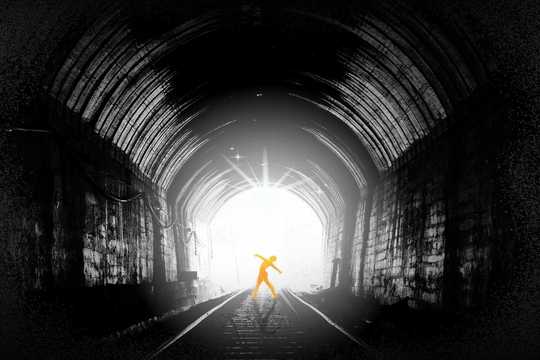

Psychotherapist Carly Mountain describes journeying into the underworld with the Dark Goddess. She says, “The antidote to the hero’s quest outwards: it calls us back into our bodies, our relationships, and our roots” [7]. Rather than blasting us out of our bodies into the cosmos, safely beyond the discomforts and challenges of our embodied trauma and complicated relationships, the feminine wisdom of the archetypal underworld journey invites us deeper in.

Inanna’s Journey to the Underworld

The mythology of the Dark Goddess can be traced back to the oldest surviving epic poem ever written., The Descent of Inanna from Ancient Sumer (modern-day Iraq). Written 4000 years ago, this epic poem of death and resurrection is twice as old as the story of Christ. It predates the Greek myth of the Gemini, which rewrites Inanna’s story from a decidedly patriarchal perspective.

A Symbolic Template for the Psychological Underworld Journey and the Transpersonal Psychedelic Experience

The Goddess Inanna descends to meet her sister Ereshkigal, Goddess of the Underworld, who is in mourning. As she descends, Inanna is stripped of her sacred garments and jewelry—symbolizing layers of her personality, her ego, and her power.

Who is Ereshkigal?

Symbolically, Ereshkigal holds all of the pain, trauma, anger, and cruel impulses hidden in the subconscious and in the body. She is Inanna’s twin, her other half or her shadow self. After years spent dwelling in the light above, Inanna chooses to meet the parts of herself that live below the surface. The parts below conscious awareness.

Fear of the underworld is warranted. In the myth, Ereshkigal destroys Inanna. Killed by her sister, she hangs lifeless on a hook in the underworld for three days before her resurrection.

The Power of Compassion

After Inanna’s death, Ereshkigal is visited by the kurgarra and the galatur—two non-binary beings made of the earth itself. They see Ereshkigal not as evil or threatening but as someone in deep pain. These beings are symbolically beyond duality while also being completely of the earth. They witness her pain and show compassion. In this moment, Ereshkigal’s vindictiveness dissolves. The power she wielded to destroy Inanna is now harnessed to bring her back to life.

Through her healing, Ereshkigal raises Inanna from the dead. Inana has integrated these disowned parts of self into her being through the journey of descent, death, compassion, and rebirth. In her rising, Inanna brings Ereshkigal with her.

Mythological Frameworks for Psychic Rebirth

So often in our psychedelic journeys, we encounter our Ereshkigal. Feelings and memories we have tried to ignore can come rushing back in overwhelming and frightening ways. Going into these experiences with an archetypal understanding of the deeper purpose and potential for psychic and spiritual rebirth can fortify us for the journey. This enables us to trust and surrender to the dissolution of self and the encounter with our underworld twin.

Mythological frameworks weave together multiple layers of consciousness. They support not only the psychedelic experience itself but the integration afterward, the process of psychic rebirth. The myth of Inanna and Ereshkigal is an example of an embodied feminine wisdom story. One that reaches back into our pre-Christian collective consciousness and guides us toward wholeness.

What myths, images, or practices might draw you closer to your sacred darkness, to the Dark Goddess who beckons you? What hidden wounds could your Ereshkigal be holding? And are you ready to meet her?

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.References

- Gimbutas, M. (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Gimbutas, M. (1974). The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images. University of California Press.

- Sjöö, M., & Mor, B. (1987). The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Jacobsen, T. (1976). The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. Yale University Press.

- Goode, S. (2016). Sheela na gig: The Dark Goddess of Sacred Power. Inner Traditions.

- Woodman, M., & Dickson, E. (1997). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Gill & Macmillan.

- Mountain, C. (2023). Descent & Rising: Women’s Stories & the Embodiment of the Inanna Myth. Womancraft Publishing.