The recent COMPASS phase IIb clinical trial sheds more light on the potential for psilocybin to help patients with depression [1]. But what do the results mean in the broad context of psychedelic research and regulation? Let’s dive into the study structure, outcomes, and the next steps for research. We’ll discuss what to know about psilocybin therapy for depression.

In 1970, the Drug Enforcement Agency designated psilocybin a Schedule 1 drug. Before that, psychiatric researchers had been studying its uses in depression and other affective disorders. The ruling halted this research, and the growing body of evidence on psychedelics and their practical uses stalled.

In the last few years, we’ve seen emerging research and excitement around psychedelics and their potential to improve lives. Since 2016, several studies have been published with promising results.

TRD, or treatment resistant depression, is an especially severe form of depression. It means that a patient has undergone two different therapies without relief. TRD is often associated with prolonged psychiatric inpatient admissions, as well as increased risk of death [2]. A 2016 open-label study showed positive outcomes when patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression received psilocybin in a controlled setting [3].

Giving Context to the COMPASS Study

In 2018, COMPASS received Breakthrough Therapy Designation by the FDA to research psilocybin as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Then in 2019, Usona Institute received the same designation for psilocybin therapy for major depressive disorder. Usona is a non-profit medical research organization with phase II trials ongoing at this time.

COMPASS’ 2019 phase I trial had 89 healthy participants [4]. This double-blind study tested placebo, 10mg, and 25mg doses of psilocybin in groups of up to six participants at a time. Phase 1 study results showed this therapy was safe for healthy individuals in a clinical setting.

A 2020 literature review included 14 recent observational and survey studies of microdosing psilocybin and LSD for depression [5]. Both substances had positive, if subtle, effects on cognition and mood. The review also showed cycling euphoric and depressive patterns and anxiety for participants.

These effects could lead to better cognitive flexibility, improving depression by decreasing rumination. But the ups-and-downs in mood remain concerning for patients.

Research like this has helped move the field of psychedelic medicine forward, but results have been small and limited. Going into the COMPASS study, there was good evidence that psilocybin was safe to use in a controlled setting with one-on-one therapy. What was not clear was the correct dosage to administer and if individuals with depression would tolerate and respond to the treatment.

What makes this latest study novel was it’s advancement as a Phase IIb trial. It’s size gives us the largest data set we have on psilocybin to date. Let’s talk about how it worked.

Psilocybin Therapy for Depression Trial Structure

This study included 233 patients across the United States and Europe. Participants were given one of three different doses of COMP360, a synthetic psilocybin. These were 1mg (a placebo), 10mg, and 25mg. Along with their assigned dosages, participants received one-on-one counseling for 12 weeks.

For their session, participants received their dose of COMP360 in capsule form. Then they lied down in a comfortable room, with specific music playing and an eye mask to limit distractions. The psychedelic experience lasted between six and eight hours.

Before beginning the trial, participants established a rapport with their trained therapists. They had to stop taking their antidepressants before the trial to avoid skewing results. According to COMPASS’ press release and results summary [6], 94% of study participants had no prior psychedelic experiences.

Afterwards, participants worked with their therapists to understand and integrate their experiences. A third-party assessor measured their depression symptoms throughout the study.

COMPASS used the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to measure the severity of participants’ depression throughout the study period [7]. This scale is often used in clinical trials to assess changes in mood related to treatment. Now let’s discuss the findings.

Results from the Largest Psilocybin for Depression Trial

COMPASS calls their results “One of the most promising innovations in psychiatry today” [1]. Yet the findings were accompanied by a steep drop in the company’s stock. Some felt that the numbers were disappointing compared to prior findings. We’ll let you decide.

The key dosage question was answered: patients in the 1 and 10mg cohorts showed no statistical difference in MADRS scores at week three. Compared to both other groups, the 25mg cohort had lower depression scores at this point. The takeaway here is that in future efficacy trials, COMPASS will focus on their 25mg dose of COMP360.

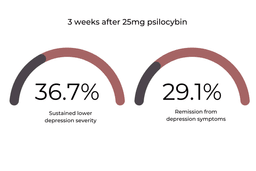

The 25mg cohort showed the most promising improvements in depressive symptoms throughout the trial. At week three, 36.7% of this group sustained lower MADRS scores, and 29.1% of this group had complete remission from depressive symptoms.

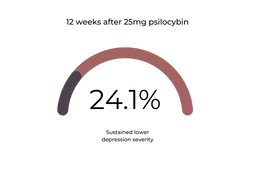

At twelve weeks, 24.1% of this group sustained their decreased depression scores [1].

These numbers showed statistical significance between psilocybin therapy and depression relief, but were less impressive compared to other research. In contrast, a smaller prior study of psilocybin for depression reported 71% of participants had a clinically significant response one week and four weeks after psilocybin[8], and a different study showed 58% of participants were in remission at 3 months [3].

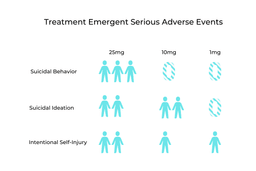

Along with positive results from the COMPASS trials came some concerning ones. These related to Treatment-Emergent Serious Adverse Events (TESAE). In the entire study, 19 separate TESAE were reported from 12 different participants. Most concerningly, seven people in the 25mg group reported suicidal ideation and self-harming thoughts. Comparatively, six from the 10mg group and four from the 1mg group also experienced these negative thoughts and feelings [1].

It’s important to point out that this population is at increased risk for these symptoms [9]. According to COMPASS, all of the study participants who reported these TESAE had experienced these thoughts before. In fact, two-thirds of the study group had previously experienced suicidal ideation, so it’s difficult to determine whether these can be associated with psilocybin [1]. Nonetheless, suicidal ideation and behavior was more prevalent in the high dose psilocybin group. A larger population of participants is needed to understand if this effect is drug related.

It’s also possible that stopping SSRIs before the study could have led to suicidal ideation in the study group. Future research will need to examine participants for these adverse events and explore whether or not they are linked to psilocybin.

COMPASS released new results from an open-label study with 19 patients who received 25mg of psilocybin (COMP360) while taking SSRIs at the same time. The outcomes were similar to phase IIb trial results with 42.1% of patients responding at 3 weeks with lower depression severity. The press release didn’t mention if the subjective experiences under psilocybin were comparable or different for those taking SSRIs.

The key takeaway is that a 25mg dose of psilocybin could be beneficial for certain people with treatment-resistant depression. As we analyze these results, we look forward to learning more about the efficacy of psilocybin therapy for depression in larger phase III trials.

Next Steps in Research for Psilocybin Therapy for Depression

This study focused on dosage, so there are still a lot of questions to be answered before COMPASS can move into commercialization and marketing.

The COMPASS study of psilocybin is considered preliminary evidence until two phase III trials demonstrate significant efficacy over a control group. While these early results are promising, much more research will need to be done before we will know if psilocybin can be a competitive treatment for TRD. One study sponsored by the Mannheim Central Institute of Health, aims to finish in 2024, is already in the works to determine efficacy [10]. COMPASS has also announced a larger phase III trial, which is set to begin in 2022.

We don’t yet know how psilocybin compares to other treatments and modalities for TRD. Another recent study [11] compared psilocybin and Escitalopram (Lexapro) for depression, and found no significant difference in preliminary results. Secondary results actually favored psilocybin, but longer trials comparing different therapies will be necessary.

In order to control for abruptly stopping SSRIs, future studies may use psilocybin in conjunction with traditional antidepressants. More research could also include subsequent doses of psilocybin or additional therapy. We still have so much to learn about medical psychedelics, and we look forward to future research.

Mushroom Therapy Near Me?

We’re years away from psilocybin therapy being offered on the consumer health market. But thanks to this latest COMPASS study and other ground-breaking research, we’re one step closer to understanding the potential benefits and risks. Every new piece of research is a building block in the foundation of psychedelic medicine.

We think psychedelics can have broad applications to improve people’s lives, and we hope the future will bring many different points of access to psychedelic treatments like psilocybin. To learn more about how we think psychedelic access could look in the future, including access to natural fungi containing psilocybin and state led initiatives, check out this article.

If you are a clinician interested in learning more about psychedelics and their medical applications, read up on Psychedelic Continuing Education for Healthcare Professionals. For interested clinicians, we provide evidence-based learning from top experts in medical psychedelics. Learn more about our programs on our Education page.

References

- Robhern. (2021, October 29). Comp360 psilocybin therapy in treatment-resistant depression: Phase iib results. COMPASS Pathways. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://COMPASSpathways.com/our-research/psilocybin-therapy/clinical-trials/psilocybin-therapy-study-results/.

- Brenner P, Reutfors J, Nijs M, Andersson TM-L. Excess deaths in treatment-resistant depression. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. January 2021. doi:10.1177/20451253211006508

- Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, Day CM, Erritzoe D, Kaelen M, Bloomfield M, Rickard JA, Forbes B, Feilding A, Taylor D, Pilling S, Curran VH, Nutt DJ. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jul;3(7):619-27. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7. Epub 2016 May 17. PMID: 27210031.

- Rucker, J., Young, A., Bird, C., & Daniel, A. (2019). Psilocybin administration to healthy participants: safety and feasibility in a placebo-controlled study. https://COMPASSpathways.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COM100945_ACNP_Rucker_ePoster_withoutQR-1.pdf

- Kuypers, K. P. C. (2020). The therapeutic potential of microdosing psychedelics in depression. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320950567

- COMPASS Pathways announces positive topline results from groundbreaking phase iib trial of investigational COMP360 psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression. COMPASS Pathways plc. (n.d.). Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://ir.COMPASSpathways.com/news-releases/news-release-details/COMPASS-pathways-announces-positive-topline-results.

- Thase, M., Harrington, A., Calabrese, J., Montgomery, S., Niu, X., Patel, M, (2021) Evaluation of MADRS severity thresholds in patients with bipolar depression, Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 286, Pages 58-63, ISSN 0165-0327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.043.

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., May, D. G., Cosimano, M. P., Sepeda, N. D., Johnson, M. W., Finan, P. H., & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 481. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

- Reutfors, J., Andersson, T. M.-L., Tanskanen, A., DiBernardo, A., Li, G., Brandt, L., & Brenner, P. (2019). Risk factors for suicide and suicide attempts among patients with treatment-resistant depression: Nested case-control study. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1691692

- Efficacy and safety of psilocybin in treatment-resistant major depression – full text view. Efficacy and Safety of Psilocybin in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov. (2020, December 17). Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04670081.

- Carhart-Harris, R., Giribaldi, B., Watts, R., Baker-Jones, M., Murphy-Beiner, A., Murphy, R., Martell, J., Blemings, A., Erritzoe, D., & Nutt, D. J. (2021). Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402–1411. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2032994

- Turkoz, I., Alphs, L., Singh, J., Jamieson, C., Daly, E., Shawi, M., Sheehan, J. J., Trivedi, M. H., & Rush, A. J. (2021). Clinically meaningful changes on depressive symptom measures and patient‐reported outcomes in patients with treatment‐resistant depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13260