Ketamine therapy has shown promise in helping reduce symptoms of mood disorders. However, ketamine has potential benefits and potential risks. It is not a miracle drug. At best, it is only one part of a larger mental health therapy regimen and patients need to manage their expectations about results. There is still little scientific data about the long-term efficacy and risks of ketamine therapy.

Ketamine therapy to help reduce symptoms of mood disorders (like depression) has shown promise in recent years, but it requires caution. Ketamine has potential benefits and potential risks. It is not a miracle drug. Although deaths from overdose are extremely rare, it has the potential to become addictive and some studies show that long-term use might cause urinary, gastrointestinal, and/or cognitive problems [1].

Admittedly, many studies about ketamine’s potential risks involve people using ketamine on their own, more often, and in greater amounts than most people receiving therapy. However, weekly maintenance therapy might be needed to sustain anti-depressive benefits [2], which might lead to dependency in some patients. Without infusions each week, the anti-depressive effects of ketamine often diminish over the weeks following ketamine treatment [3]:

Risks Associated with Ketamine

A growing concern is that many individuals using ketamine on their own for ’self-treatment’ may actually be developing dependence to the drug and are at risk for negative effects. Some frequent users have reported physical withdrawal symptoms, including irritability, shaking, sweating, and trouble sleeping [4].

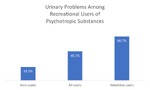

Urinary problems are also possible. One study found that 60.7% of recreational ketamine users reported urinary issues, compared with 40.1% of people who used other “psychotropic substances,” and 18.5% of non-users [5]:

Indications for Ketamine Treatments

Ketamine is an effective painkiller, which makes users more vulnerable to injury [1]. In fact, ketamine was originally developed to create more effective anesthetics [6]. It is still widely used as an anesthetic and painkiller by many hospitals.

Ketamine’s legal status (schedule 3 medication available through off-label prescription) has led to a rapid growth in ketamine clinics around the country with a focus on mental health. Unlike SSRI medications like Prozac or Zoloft that mainly target the neurotransmitter serotonin, many studies show that ketamine mainly targets the neurotransmitter glutamate but modulates many transmitter systems [2]. There is hope that this difference could help patients who don’t respond to SSRIs and other standard anti-depressive treatments.

However, there is still no consensus about how much or how often ketamine should be used for mental health purposes, which makes some researchers concerned. Perhaps the most common therapy method now involves [1]:

- IV 0.5 milligrams of ketamine per kilogram of patient body weight

- Ketamine infused for 40 minutes in each session

- 6 sessions, usually with at least 48 hours between each session

- Psychotherapy as part of the treatment known as “ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP)”

- Protocols can vary depending on the clinic

Esketamine vs KAP

Esketamine (marketed as Spravato), a chemical compound closely related to ketamine, was developed through clinical trials to deliver the benefits with fewer risks. However, one of the “risks” in this case is the psychedelic effect, which some therapists think is essential to helping patients. Esketamine appears to be an attempt to turn ketamine into a medication that can be self-administered by patients through a nasal application with ongoing therapeutic benefit from repeated doses of the drug, similar to SSRIs.

On the other hand, ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) helps patients build skills and strengthen the therapeutic process to have greater chances at longer term symptom reduction and personal growth. A common approach for KAP is to have a doctor prescribe ketamine lozenges for the client to work with a therapist or psychologist.

Caution and Ethical Guidelines

Patients should be cautious of ketamine clinics that seem too good to be true. Dr. Wesley C. Ryan has warned: “A not insignificant minority of clinics offer ‘package deals’ on ketamine, grossly misrepresent the treatment by suggesting it is a ‘cure’ for depression or make unsubstantiated and exaggerated claims about efficacy” [7].

Recognizing the current unknowns about ketamine therapy, the Kriya Institute has developed “Ethical Guidelines for Ketamine Clinicians“ [8]. For example, “the ethical ketamine clinician understands and appreciates the importance of integrative psychiatric and psychological care for therapeutic ketamine patients (i.e., using multiple strategies to get better and stay well). The ethical ketamine clinician takes the time to explain this to each patient and helps patients to connect to these resources in their community.”

The potential of ketamine therapy to help reduce symptoms of mood disorders is a promising development. But ketamine has potential benefits and potential risks. It is not a miracle drug for all the problems of patients suffering from mood disorders. That should always be kept in mind.

References

1. Sassano-Higgins, S., Baron, D., Juarez, G. et al. (2016). A Review of Ketamine Abuse and Diversion. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 718-727. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22536

2. Phillips, J., et al. (2019). Single, Repeated, and Maintenance Ketamine Infusions for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(5), 401-409. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070834

3. Shiroma, P., et al. (2014). Augmentation of response and remission to serial intravenous subanesthetic ketamine in treatment resistant depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 155, 123-129. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.036

4. Garg, A., Sinha, P., Kumar, P., Prakash, O. (2014). Use of naltrexone in ketamine dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1215-1216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.004

5. Tam, Y., Ng, C., Wong, Y. et al. (2016). Population-based survey of the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in adolescents with and without psychotropic substance abuse. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 22(5), 454-63. 10.12809/hkmj154806

6. Mion, G. (2017). History of Anaesthesia. The ketamine story – past, present and future. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 34(9), 57-575. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000638

7. Ryan, W. (2020). Commentary (Ethical Guidelines for Ketamine Clinicians). Journal of Psychedelic Psychiatric Therapy, 2(4), 20-23.

8. Bennett, R. (2020). Ethical Guidelines for Ketamine Clinicians. Journal of Psychedelic Psychiatric Therapy, 2(4), 19-20. https://www.kriyainstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/JPP-Ethical-Guidelines-for-Ketamine-Clinicians.pdf

Photo by Jonathan Klok on Unsplash