Kratom has both saved and ruined lives. Clearer labeling could help.

Nicole Sanchez’s Story

After weaning off Suboxone, Nicole Sanchez was opioid free for 11 years—that is, until she walked into a Sunoco gas station and purchased what she thought was an energy drink.

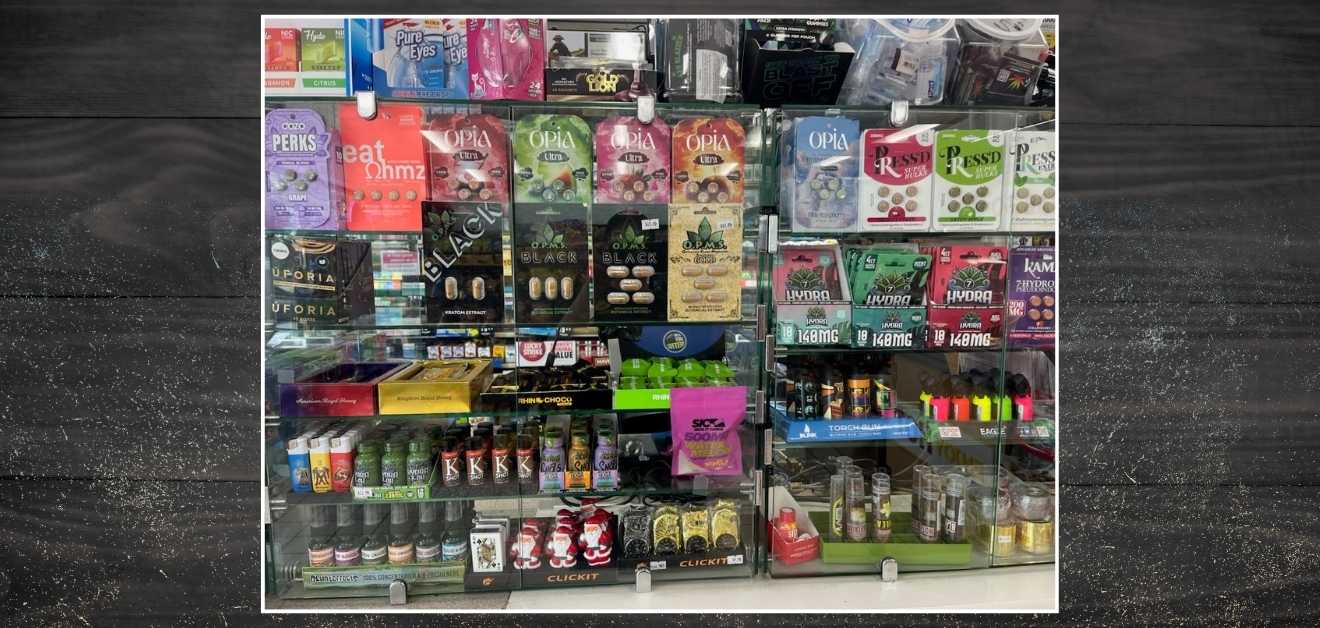

It wasn’t too long before Sanchez was spending $60 per day on three little bottles of OPMS’ Black Liquid Kratom Extract. Eager to find a more affordable alternative, she picked up some Opia tablets for the gentler price tag of $30 for four doses.

Those Opia tablets contained 7-Hydroxymitragynine (7-OH), a naturally occurring alkaloid found in the kratom plant (Mitragyna speciosa in Latin). Seven-OH makes up less than two percent of natural kratom, but synthesized 7-OH products have significantly cranked the dial on the dose.

“None of these websites selling kratom had any warning about it being addictive, or any information about it basically hitting the same receptor.”

— Allison Hoots, Esq.

“I had no idea it was way more potent than the kratom extract,” says Sanchez.

“You would think my brain would be on my side, but addiction has turned it against me,” says Sanchez. The supermarket where Sanchez works shares a parking lot with the gas station that sells an impressive variety of 7-OH products, and every day she has to fight the urge to walk over there on her break and buy a fix. “The mental obsession is indescribable,” she says, “It’s relentless.”

“I hate to call it a relapse,” says Sanchez’s doctor, James Kurt Grovenburg, MD. “It’s more like a new lapse.” He explains that Sanchez is one of many patients to “get blindsided by these products, not realizing that they can be addictive.”

Kratom’s Origins and Modern Risks

Kratom is indigenous to Southeast Asia, where farmers have traditionally used it for an energy boost. The leaves of the plant are customarily chewed fresh or dried and then brewed into tea. The candy-flavored isolates sold in smoke shops, gas stations, and convenience stores across the USA, however, are unlike anything you’d find in the Cambodian countryside. That may be why kratom is also sometimes called “gas station heroin” or “hippie heroin.”

The Crackdown on 7-OH

As the addiction epidemic rages on and people like Sanchez struggle to overcome substance use disorder, 7-OH is the new proverbial wolf in sheep’s clothing. That’s perhaps why US Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) Robert Francis Kennedy Jr. (RFK Jr.) has recently launched a crackdown on 7-OH products.

In a press meeting at the end of July 2025, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Marty Makary asserted, “7-OH is not just ‘like’ an opioid … it is an opioid.” Makary cited a scientific paper that found 7-OH to be 13 times more potent than morphine. (Another paper found 7-OH to be 10 times stronger than morphine.)

Sanchez says, “Who would have thought that a simple find in a gas station would consume my life as much as any opiate ever did? The truth is, it’s worse than any illegal narcotics because of its locality and accessibility.”

“It needs to move to regulation sooner than later, is the bottom line,” says Grovenburg. “The promotional advertising needs to be clamped down on for sure.”

In other words: 7-OH is much more potent, much more addictive, and much more dangerous than manufacturers want you to believe.

Research has found that 7-OH binds to the human mu-opioid receptor with approximately nine times the affinity as mitraginine, the other major alkaloid found in kratom. Mu opioid receptors are the primary target of opioid drugs like morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl. Mu opioid activity slows pain signaling and produces analgesic effects.

The FDA’s announcement states, “The FDA is specifically targeting 7-OH, a concentrated byproduct of the kratom plant; it is not focused on natural kratom leaf products.”

But that doesn’t mean that the whole kratom leaf is totally safe either. Should the FDA expand its scope to include all kratom preparations?

“I didn’t realize it was addictive.”

Kratom’s appeal cuts across social lines, drawing in biohackers, natural living advocates, and low-income workers alike. With both energizing and calming effects depending on the dose, kratom can serve as a social lubricant, energy booster, productivity hack, and sleep aid. Patients with various types of pain appreciate the relief afforded them by kratom, and others have even used the plant to help them quit using opioid drugs.

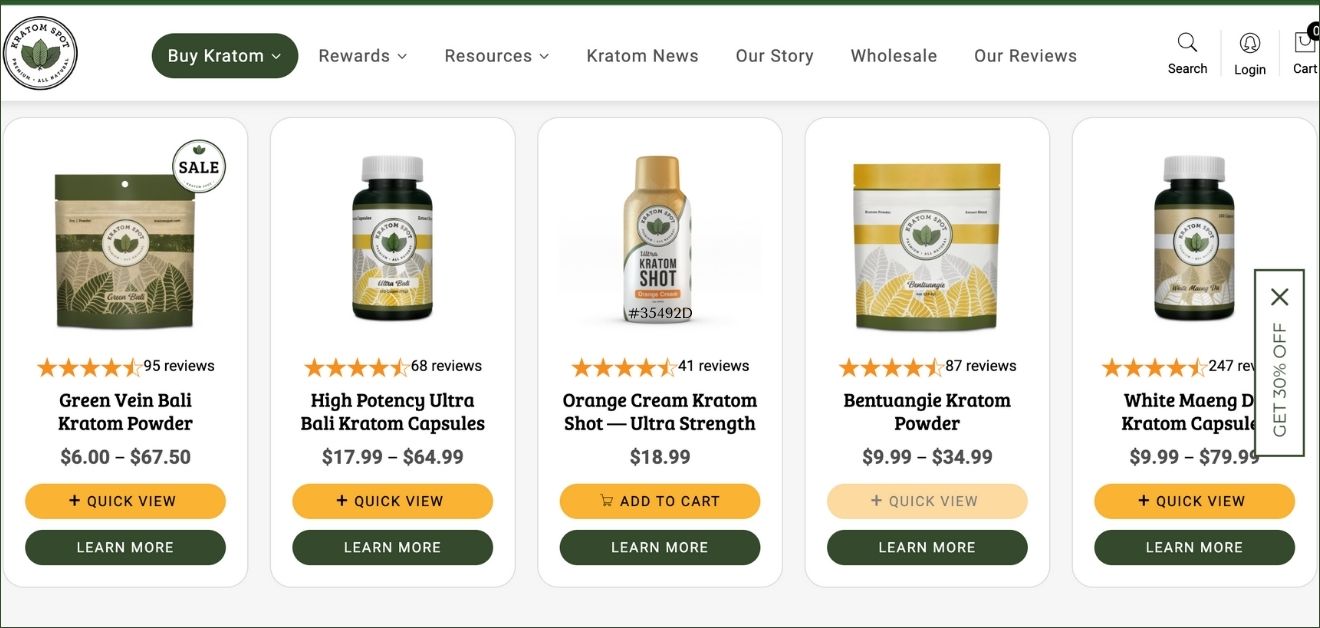

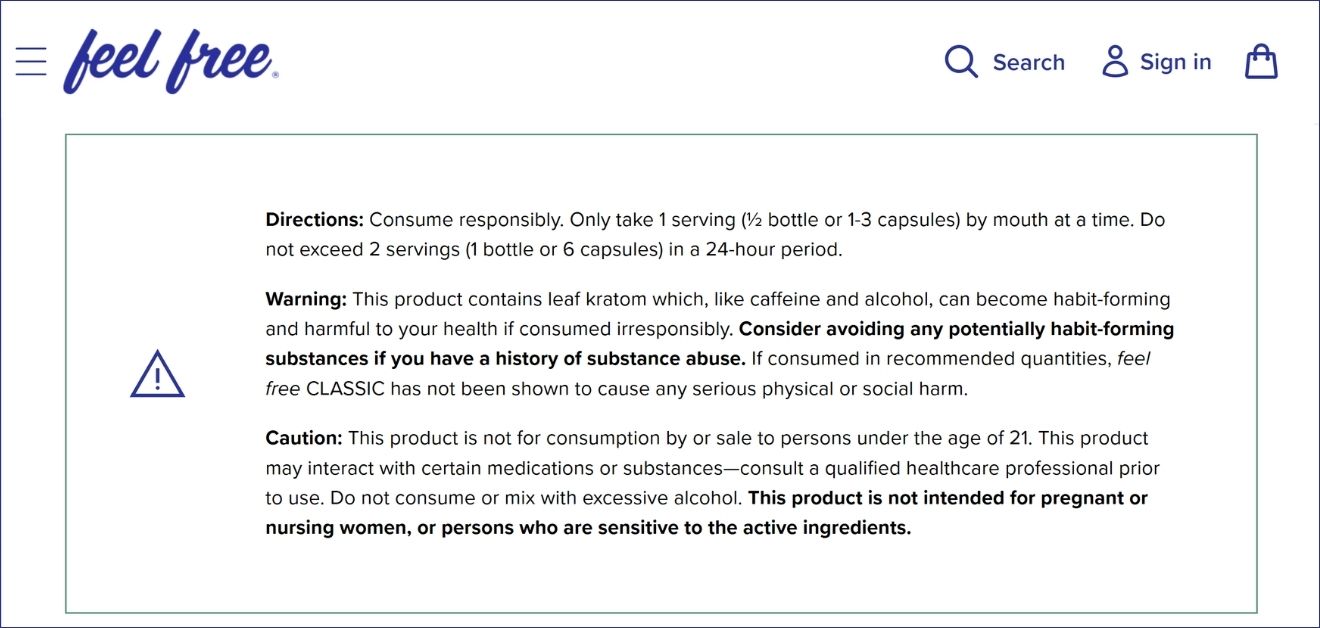

There’s just one problem: Most kratom products don’t carry any warning about the plant’s potential for addiction.

As the popularity of kratom grows, so too does the number of people whose lives have been turned upside down by kratom addiction. Kratom advocates are quick to minimize the risks, or to say that it’s only 7-OH that can cause harm, but we’re hitting a crisis point that’s getting harder and harder to ignore.

As nefarious as 7-OH may be, the naturally-derived kratom it’s made from that gives rise to it, is also addictive.

Allison Hoots’ Introduction to Kratom

After undergoing two back surgeries, Allison Hoots, Esq., an attorney and mother of two, found herself addicted to the oxycodone prescribed by her surgeon. Eager to quit but plagued with horrible withdrawal symptoms when she tried to decrease her usage, Hoots signed up for an e-course through opiateaddictionsupport.com. It was there that Hoots learned about kratom as a natural aid for both pain and opioid withdrawal. A quick Google search and a few clicks later, she’d placed an order for kratom leaf powder.

The package arrived when Hoots was in the throes of opioid withdrawal. She recalls feeling “that same opiate energy rushing through my body” from her first dose of kratom. That day, she was able to clean her home and feel optimistic about her recovery. She ordered more kratom powder, trying different varieties. “I had it in cute little jars with labels on them,” she recalls. “Kratom came easy. It looked like an herb; it felt natural. My hippie side really liked that.”

A savvy bargain hunter, Hoots visited several kratom websites in those months. “If you shop around, your first order is 20% off, so you could just go from site to site, and it’ll come to your house. For any drug addict, that’s dangerous.” Only Hoots didn’t realize that she was addicted. The e-course didn’t mention that kratom could be habit-forming. (I emailed Matt Finch, the founder of the course Hoots purchased, but I didn’t receive a reply to my query.) “None of these websites selling kratom had any warning about it being addictive, or any information about it basically hitting the same receptor,” Hoots explains.

From Dependence to Recovery

To feel stable, Hoots had to take kratom every few hours, usually ending the day with a hefty dose before bed. “I’d do the red at night and the green in the morning—it was a whole scheme,” she said. Sometimes she skipped the capsules altogether and instead “parachuted” the powder, wrapping it in a bit of tissue and swallowing it quickly.

Hoots’ reality check came while calling in a large order of kratom. “The woman on the phone was like, ‘Be aware, you can get dependent on this.’” Hoots recalls. “That was the first time that a little seed was planted, like, this isn’t a freebie.”

But when Hoots tried to stop taking kratom, she realized she was in trouble, “I was right back where I was with opiates,” she says, “the withdrawal was awful, even worse than with opiates.” Seeking out support for her kratom addiction, Hoots found that “there was a lot of gaslighting,” and people either denied that kratom was addictive or insisted that addiction was exceedingly rare.

With Grovenburg’s help, Hoots was able to get off of kratom through a six-month outpatient treatment. The treatment plan included several pharmaceutical medications to stabilize Hoots as she withdrew from the kratom leaf powder.

Grovenburg, who has worked in addiction medicine for over two decades, describes kratom as “a dirty drug.” He explains, “It definitely affects the opioid receptor, including the kappa receptor. It creates a classic addiction pattern. At some point in time, you can never get enough. At the receptor level, it follows the classic pattern of addiction.”

How Hard Is It to Treat Kratom Addiction?

How hard is it to get off of kratom, anyway? Since it’s a natural substance and not a synthetic drug, is it really as hard as quitting, say, oxycodone or morphine?

“It’s harder,” says Grovenburg, who points out that there are standard protocols for getting people off of opioid drugs. With kratom, however, he says he needs to be more creative. He often prescribes buprenorphine (also sold under the brand name Subutex), a medication that binds to the same receptors in the brain as opioids, but activates them less intensely. A case series published in 2021 also reports success in managing kratom dependence in veterans with buprenorphine/naloxone (sold under the brand name Suboxone).

Medical Treatment Challenges

Grovenburg also typically prescribes a short course of benzodiazepines (drugs like Xanax or Valium) to help with agitation, plus clonidine to control blood pressure and a mood stabilizer (often Seroquel) to help with insomnia while patients are withdrawing from kratom. In other words, kratom addiction isn’t simple to treat.

The patients in Grovenburg’s medical practice include people who became addicted to kratom while trying to get off of opiates, as well as individuals without any addiction history who got hooked directly on kratom.

A challenge to treatment is the ubiquity of kratom products. “We talk about people, places, and things,” explains Grovenburg, referring to the importance of avoiding settings and situations where one might feel tempted to use their drug of choice. “But it’s pretty hard to avoid gas stations.”

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.That’s especially true for Sanchez, who works next to a Sunoco gas station. Sanchez tried asking the gas station attendant not to sell her kratom products. “He looked at me like I was a pathetic human being,” she says. “The next day, he sold it to me anyway.

It’s not his fault. Obviously, he has a job to do, and refusing the store profit is not it.”

Turning to Ibogaine

Because so few conventional practitioners understand kratom, and because the management of withdrawal is so challenging, many people with kratom addiction turn to ibogaine for help.

Ibogaine is the active alkaloid found in the root bark of the iboga (Iboga tabernanthe) bush. The bush is indigenous to Cameroon and Gabon, where people have ceremoniously used it in spiritual ceremonies and rites of passage. It. It has also shown promise in the treatment of opioid use disorder, including in cases in which conventional treatment has been unsuccessful.

Jonathan Dickinson, CEO of Ambio Life Sciences, helps clients overcome kratom addiction. “When somebody comes down to do ibogaine,” he explains, “there’s a little bit of a complication with kratom because it has some cardiac effects. So typically, we have to stabilize people here on morphine for a couple of days.”

Talia Eisenberg, co-founder of Beyond Ibogaine in Cancun, explains that kratom can be harder to kick than many other opioids. “Our program for getting people off of short-acting opioids is 10 days,” she tells me. “But the program for getting people off of fentanyl or kratom is 14.”

Why Kratom Is Harder to Quit

In his eighth decade of life, Barry Rossinoff has been supporting individuals with opioid use disorder longer than most others in the field. Rossinoff and the team at IbogaQuest have helped people get off of a myriad of opioids, including heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, fentanyl, and kratom. In recent years, however, Rossinoff has seen an alarming surge in the number of clients reaching out for help with kratom addiction.

When I ask him if it’s harder for people to quit heroin or kratom, Rossinoff barely lets me finish the question before responding, “kratom.” He explains, “kratom, particularly the extracts that are now ubiquitous in many places in the US, contain various substances that can be, for lack of a better word, ‘sticky.’”

Like Dickinson and Eisenberg, Rossinoff sees ibogaine helping many people kick kratom. But after patients leave, they report some bumps in the road. “About two weeks after treatment, they tend to get PAWS,” he explains. PAWS, or Post Acute Withdrawal Syndrome, refers to symptoms like irritability and restlessness that can persist after the initial drug withdrawal is over.

Going Cold Turkey on Feel Free

Many people with kratom use disorder can’t afford treatment—or don’t know where to find it. For some, quitting cold turkey is the only option. Dog trainer Noah Joseph Urbina is one of those who faced the challenge head-on without medical help.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Urbina became hooked on Feel Free—a potent kratom concentrate drink now tied to a wave of addictions. Urbina estimates that he spent about $100 per day—$3,000 a month—on his habit. At first, he limited himself to purchasing just two or three bottles per visit to his local produce stand, “but then I’d go back to the place a couple of times a day,” he says, “the delusions we tell ourselves that we aren’t addicted.” Eventually, Urbina began arriving at the produce stand before it opened, hoping they’d let customers in early. He noticed a few others lingering in the parking lot with the same idea. “Like a couple of junkies in an alley, we’d talk about splitting a case just to get our fix,” he recalls.

Urbina explains that he’d taken kratom leaf powder in the past without developing any kind of tolerance or dependency. “But Feel Free was something else,” he says. To avoid withdrawal symptoms, Urbina would wake at night to drink the tonic.

Withdrawal and Recovery

Urbina quit drinking Feel Free by first tapering down his usage and then stopping cold turkey. “I really underestimated how bad it was going to be to ride it out without any kind of help,” he tells me.

It took Urbina about two weeks to get through the worst of the withdrawals, describing it as “nonstop suffering.” He explains that even on day 12, he was “bedridden, suffering, trembling, shaking.” Urbina also experienced akathisia, an extreme restlessness and inability to sit still. “I was horse-kicking in bed to the point I thought my back was going to break,” he says.

Since Urbina first started drinking Feel Free, Botanic Tonics, the makers of the product, have reformulated the drink and added a warning to their webpage.

The Pushback Against Regulation

Many kratom users outright deny that kratom is addictive, or suggest that only people with a history of opioid use disorder are at risk for getting hooked on the plant. Others make the “anything can be addictive” argument, incorrectly asserting that kratom dependency is a psychological habit and not a physical addiction. (The lady doth protest too much, methinks.)

It doesn’t help that influencers and biohackers often promote kratom as a wellness elixir. Eisenberg shared that a former professional athlete recently came to Beond Ibogaine to treat his addiction to Feel Free. “He heard about it on some famous biohacker’s podcast,” she explains. “Because a biohacker validated it, he didn’t think it was addictive.”

Influencers like Joe Rogan have also made kratom seem glamorous, minimizing its risks with guests like researcher Hamilton Morris and musician and comedian Reggie Watts.

A quick search for “kratom addiction” in PubMed (a database of studies and other medical literature) yields over 200 entries dating as far back as 2007. Many articles warn about the risks of kratom addiction, withdrawal, and life-threatening toxicity.

Debates Around Kratom Addiction

Thankfully, the kratom leaf is only a partial agonist of opioid receptors, meaning it doesn’t bind the receptors as strongly as classic opioids. A 2019 review estimates that opioids are more than one thousand times more likely to kill somebody than kratom—but the data is over six years old, and doesn’t consider kratom concentrates or 7-OH products. Although kratom is less likely to make a user stop breathing than heroin, there have been documented deaths associated with kratom, including the death of Tyler Wall, the personal trainer of YouTuber MrBeast.

A survey of kratom leaf users in Southern Thailand also reports that regular consumers of kratom leaf say they’ve become addicted—so it’s not just an American thing.

Why do so many people and companies deny that kratom binds many of the same receptors as hard-hitting opioid drugs like heroin and oxycodone?

Perhaps because kratom has significantly helped many people in profound ways—some have used kratom instead of opioids. Others credit kratom for assisting them in quitting using other opioid drugs altogether—and the research does indeed support such usage of the plant.

Folks who have experienced benefits from kratom also fear that the plant will become regulated or banned, creating barriers to access for those who may need it the most. After all, if kratom becomes regulated, it might be easier to find fentanyl on the street than kratom leaf. This pattern happened when regulators made heroin illegal—people found other, more nefarious drugs.

In 2016, the DEA shocked kratom advocates by announcing plans to classify the plant’s main alkaloids—mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine—as Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). That’s the government’s strictest category, reserved for substances deemed highly addictive without any accepted medical use—the same legal tier as heroin and LSD.

Public Response and FDA Distinctions

The announcement ignited a firestorm. Thousands of kratom consumers, many of whom used it to manage chronic pain or as an alternative to opioids, flooded the DEA with letters. Scientists warned the move would shut down research they could fully understand the plant’s risks and benefits, and lawmakers from both parties urged the agency to reconsider.

Just weeks later, in a rare reversal, the DEA withdrew its emergency scheduling notice. Instead, it opened a public comment period and received more than 23,000 submissions, the vast majority of which opposed the ban.

That may be why this summer’s letter to healthcare professionals from the FDA explicitly distinguishes 7-OH from kratom. It states: “7-OH is found in trace amounts in the kratom plant leaf. But this is not our focus. Our primary concern is the concentrated form of 7-OH. This distinction is an important one. These concentrated 7-OH opioid products are far more dangerous than traditional kratom leaf products.”

The FDA has also put out a report on 7-OH, which includes a specific section that explains the difference between 7-OH products and kratom. There’s also an entire page for consumers.

The FDA doesn’t actually schedule drugs; that’s the DEA’s job. This crackdown just means that they’re building a case for stricter regulation. The FDA’s input—along with recommendations from the Department of Health and Human Services and comments from the public—will then be considered by the DEA.

But what if this increased attention results in 7-OH being moved to Schedule I? That would make it nearly impossible for people to legally access the drug, even with a doctor’s prescription.

“They want to look like they’re tough on science, but they’re cherry picking data”

— Michele Ross, PhD

Concerns About the 7-OH Crackdown

Michele Ross, PhD, is a neuroscientist and the author of Kratom is Medicine (2021). She claims that HHS’s language around the 7-OH crackdown is both alarmist and theatrical.

“They want to look like they’re tough on science, but they’re cherry picking data,” she says. “The way they were talking about it, it’s as if it is this mass crisis where we need to take these products off the market because only children are using them.”

Ross is a scientific advisor at 7-HOPE Alliance, a group dedicated to public outreach and education around 7-OH. Citing yet unpublished data from a survey of 7-OH users she helped conduct, Ross tells me that “Seventy-five percent of 7-O[H] users are using it for chronic pain. The average age of kratom users is 43.” Ross insists: “It’s not a party drug. There are 80–year–olds with back pain, there are veterans, there are regular people saying, ‘this got me out of bed for the very first time, I can take care of my kids, I can get off welfare.’”

Like many, Ross fears that this new crackdown may result in a ban on 7-OH products. “Overnight, one million users would become criminals, and that doesn’t make sense.” One client even told Ross that if 7-OH were made illegal, he would pursue death by suicide.

“I’m terrified,” says Ross. “I’m holding the hands of thousands of people across the States who are freaking out about bans. A lot of patients feel very marginalized and stigmatized.” Already, several US States have enacted their own bans on kratom beyond just 7-OH.

Regulatory Suggestions and Product Warnings

Ross agrees that regulators should enact some kind of restriction.. “Do I think that there should be a regulatory framework for all kratom and kratom-derived products? Yes, absolutely.” She suggests something similar to the Tobacco Control Act, wherein age gating, third-party testing, and transparent safety warnings would be required, and marketing to children would be forbidden.

Ross also has concerns about drinks like Feel Free, which comes in a small bottle reminiscent of a “nip” bottle—the tiny, tiny bottles of liquor sold on airplanes. She also points out that Feel Free contains kava (Piper methysticum), another herbal sedative that may have harmful effects when combined with kratom. “These products have gone through phony studies,” says Ross. “For example, the Feel Free shots… they only looked at really low doses—one fourth of this mini nip bottle, which isn’t how people are using it. I wanna see what the whole bottle does. They’re advertising it like it’s a new CBD, and it’s not,” she says.

The Road Ahead

As more and more cases of toxicity, addiction, and death involve kratom and its isolates, regulation seems to be a matter of when—not if.

An analysis from 2018 states “kratom appears to have pharmacological properties that support some level of scheduling,” and “appropriate regulation by the FDA is vital to ensure appropriate and safe use.” More than seven years have passed since that analysis was published, and it doesn’t focus on kratom concentrates like Feel Free, nor does it address 7-OH products.

If RFK Jr. succeeds in restricting 7-OH, it could prevent countless uninformed consumers from unknowingly developing an opioid addiction—hopefully without leaving pain patients scrambling.

But even then, unregulated kratom leaf powder and “wellness” products like Feel Free would still be sold without the requirements of clear warnings, leaving the public unaware that these, too, can act upon opioid receptors and cause addiction.

Until there’s a requirement for transparent labeling and consumer education, we’ll continue to see people using these products without realizing they can cause dependence and withdrawal.

So what will it take to get kratom products clearly labeled to protect consumers? “It’s probably going to take some famous person getting addicted, or some politician’s kid dying from kratom toxicity,” speculates Urbina. “My suffering was so severe,” he continues, “I now understand how and why somebody can dedicate their life to a cause.”