Here’s our MDMA-assisted therapy guide for everything you need to know about this novel treatment approach. When combined with therapy, MDMA is proving helpful for PTSD and other mental health conditions. Learn more about the effects, dosage, therapeutic approach, and clinical trial findings below. Ready to learn more? Take our online MDMA course for advanced topics on MDMA therapy.

Drug Class

MDMA is an amphetamine derivative classified as an empathogen or an entactogen due to the effects users experience. While not a classical psychedelic, MDMA (C₁₁H₁₅NO₂) is a member of the larger group of ring-substituted phenethylamines, which includes mescaline. MDMA, an empathogen, is distinguished by social openness, increased empathy, social communion, and oneness, among other things.

What is MDMA?

MDMA is a small organic compound known as a monoamine alkaloid, structurally and chemically related to amphetamines. Its amine group is methylated, which makes it closely related to methamphetamine, although its pharmacology and effects are quite different.

Chemists characterize MDMA by the presence of the 3,4-methylenedioxy ring. It occurs in natural compounds, including myristicin (found in nutmeg) and safrole (present in sassafras). Chemists can synthesize MDMA from natural product sources such as safrole or isosafrole, or organic precursors used in industry and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The key distinction between MDMA and amphetamines is the addition of the methylenedioxy group (-O-CH2-O-). This attachment gives it a resemblance to the structure of mescaline.

From the Streets to MDMA-Assisted Therapy Offices

For decades now, following MDMA’s scheduling as a controlled substance and its subsequent illegality, it has been relegated to the streets and recreational use. However, this is rapidly changing thanks to more research and clinical trials.

Decades of research investigations have shown MDMA’s psychotherapeutic potential. Here’s a quick look at the MDMA timeline. To learn more about the psychotherapeutic applications of MDMA, please take a look at this list of highlighted literature and news below:

Early Development and Recognition of MDMA

- 1912 – German company Merck develops MDMA as a blood clotting compound and patents the substance without recognizing its psychoactive effects.

- 1965 – Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin rediscovers MDMA by synthesizing it himself.

Regulation and Research Milestones

- 1985 – US Congress passes a new law giving the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) authority to level an emergency ban on any drug that it thought might be a public danger. In July, the DEA used this power for the first time to ban MDMA.

- 1988 – Authorities officially place MDMA on the Schedule I list of controlled substances.

- 1992-1995 – FDA grants final approval for a Phase I clinical trial with Dr. Charles Grob.

- 2000-2002 – MAPS conducts the first-ever MDMA phase 2 study in Spain. It ended early due to political pressures.

- 2004-2016 – MAPS sponsors six phase 2 clinical trials investigating MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment in the USA, Canada, and Israel. One hundred five participants received MDMA in these studies.

- 2014-2018 – Pilot studies conducted on MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treating social anxiety in autistic adults, anxiety related to life-threatening illnesses, and cognitive behavioral conjoint therapy (CBCT) for couples where one partner had PTSD.

- 2017 – FDA grants a “Breakthrough Therapy” designation for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD.

Recent Developments and FDA Approvals

- 2019 – Several companies file patents for MDMA or related compounds. MAPS maintains an “anti-patent strategy” and does not file patents for the use of MDMA until 2022.

- 2019 – FDA approves MAPS’ application for an expanded access program for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. The program permits 50 patients with PTSD to access MDMA treatment.

- 2021 – MAPS changes the name “MDMA-assisted psychotherapy” to “MDMA-assisted therapy.”

- 2021 – The first Phase 3 trial of MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD replicates earlier studies and provides further evidence that MDMA-assisted therapy may be a safe and effective treatment for PTSD.

- 2021 – First Phase 3 clinical trial results of MDMA published by the journal Nature Medicine.

- 2021 – Drug sponsors release plans to develop MDMA for other indications and in combination with other drugs.

- 2022 – Completion of the second Phase 3 trial for MDMA-assisted therapy in moderate to severe PTSD, confirming its efficacy and safety in a broader patient population, as previous trials did not include moderate PTSD.

Continued Research and Regulatory Process

- 2023 – Nature Medicine published the second phase 3 trial results.

- 2023 – Preliminary topline results from the long-term observational follow-up study on MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of PTSD show evidence of durable improvements in PTSD at least six months after the last dosing session.

- 2023 – MAPS PBS submits a New Drug Application (NDA) for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD treatment to the FDA in December, starting the 6-10 month review process by the FDA.

- 2024 – Expected completion date of the long-term follow-up clinical trial titled “Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness of MDMA-Assisted Therapy for PTSD,” which will provide preliminary evidence of the efficacy persistence from phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials.

- 2024 – FDA rejects Lykos Therapeutics (formally known as MAPS PBC) new drug application to market MDMA-assisted therapy as a psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD. The FDA requests an additional phase 3 trial.

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.What is MDMA-Assisted Therapy?

MDMA-assisted therapy involves talk therapy alongside the ingestion of MDMA. Researchers and clinicians often describe three distinct therapy phases: preparation, the acute MDMA experience, and integration. The non-psychedelic elements of this approach are essential for both effectiveness and safety.

Preparation Phase

Various approaches to preparation have been developed, from diet to psychotherapy. In clinical trials, participants typically attend three 90-minute talk therapy sessions (unless therapists clinically indicate more sessions) with two trained therapeutic professionals who will be in attendance during the MDMA session. During this time, therapists develop a therapeutic alliance and trust and explore the nature of the individual’s struggles.

These preparatory sessions help patients by familiarizing them with session logistics and the therapeutic approach the therapist will use. In this manner, they nurture the participant with a sense of comfort and safety in a therapeutic setting. The preparation period also offers participants a vital time to address questions and concerns and guidance on how to respond to the memories and feelings that could arise during the MDMA treatment session, further developing the therapeutic alliance.

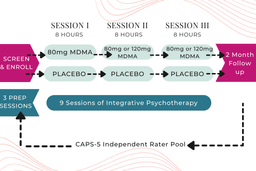

Example MDMA Treatment Flow (Dosing Varied Across Studies)

The therapists prepare the patient for the psychedelic session in several ways, with a particular emphasis on curiosity and remaining open to whatever comes up during the session (“Where do you feel tension in your body?”; “How does this memory make you feel?”). For PTSD studies, the preparation sessions are a time to converse on the trauma history of the participant and how they can psychologically process these past events under the effects of MDMA.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the preparation period is helping participants understand how therapists will use the non-directive therapy approach. This approach employs empathetic presence and rapport while focusing on invitation rather than direction. By doing so, the facilitators can assist the participants in accessing their inner healing intelligence. Accessing one’s inner healing intelligence is done solely by the participant with gentle help from facilitators. By tapping into one’s inner healing intelligence, the body can initiate its own healing process.

Set and Setting in MDMA Therapy

During the MDMA session, ‘set’ and ‘setting’ are considered paramount. ‘Set’ refers to mindset—a complex mix of more transient phenomena like expectation and mood and more enduring phenomena like personality and past experience. ‘Setting’ refers to the context or environment in which the session takes place, including basic factors like the comfort and aesthetic quality of the room and more complex factors like the quality of the relationship with the clinicians and the mood they help to set.

While many modern clinical trials occur within clinics or research institutes, the session rooms are made to appear as comfortable living rooms. The comfortable living room setting must be private and free of interruption. It should also be quiet and only allow minimal external stimuli. The room should be decorated with pleasing artwork and/or flowers, providing an aesthetically pleasing ambiance. Any negative or powerful images should be avoided.

Session Environment and Structure

The comfort provided will likely be a futon, couch, or similar that is off the floor and enables the participant to either lie down or sit up with pillow support. Blankets should be provided for temperature control. Two comfortable chairs flank the participant so that the co-therapists can sit. From here, the two therapists in attendance can assist with their non-directive approach during the 6- to 8-hour-long session.

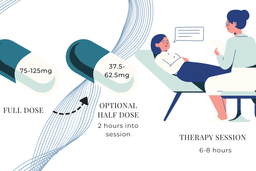

The participant can sit or lie on a couch, is often encouraged to wear a sleep mask to go inwards, and, at times, listen to a carefully selected playlist of music. Oral ingestion of a capsule of synthesized MDMA is the route of administration in clinical settings. The participant ingests a full dose (75-125 mg) to start and an optional second dose (half the quantity of the first) about two hours into the session. The session will typically last for 6 to 8 hours.

Therapeutic Approach and Support

The therapists offer support through a non-directive approach, meaning they follow where the participant goes in their experience, and they may ask questions for reflection by the participant. A common therapeutic approach during psychedelic sessions is to be inner-directive or non-directive, as described in the MAPS MDMA Treatment Manual.

Attentive but usually silent, supporting the emerging process and offering assistance and guidance if needed. In addition to listening and responding to the patient when they speak, the therapists offer little analysis of the material but may ask questions for the patient to reflect on what is coming up for them. In clinical trials, participants have 3 MDMA sessions.

Integration Phase

Immediately after the MDMA session and in the following days, a process of integration is facilitated by the therapist, which consists of three 90-minute talk therapy-only sessions (more sessions may be provided if clinically indicated). During these conversations, the participant has the opportunity to process, make sense of, give meaningful expression to their psychedelic experience, and receive therapeutic support for any challenging issues that may come up during the MDMA session.

Summary of Trial Findings

Phase 2 Trials and Early Findings

Across six Phase 2 trials (105 participants) following MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, 54% of participants did not meet the criteria for PTSD, compared to 23% in the control group. At long-term follow-up, this increased to 67.0%. Most participants also reported other benefits, including improved relationships and well-being, better sleep quality, and post-traumatic growth.

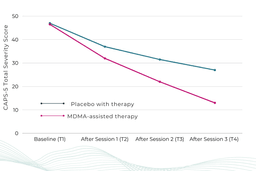

The first Phase 3 trial replicated findings from Phase 2 trials. MAPS summed up the study results by saying:

In this first Phase 3 trial of any psychedelic-assisted therapy, participants who received MDMA-assisted therapy reported a significant reduction in severe PTSD symptoms compared to those who received placebo with therapy (p<0.0001), successfully achieving the pre-specified primary endpoint for the trial. In fact, 67% of the group who received MDMA, compared to 32% of the group who received a placebo, no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis after three treatment sessions. [Additionally], participants treated with MDMA-assisted therapy had statistically significant reductions for the key secondary endpoint of functional impairment relative to placebo with therapy (p=0.0116).

To read the press release about the success of the Phase 3 trial, please click here.

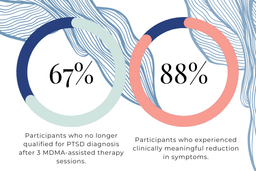

The key finding of the first MAPS Phase 3 study of MDMA-assisted therapy for chronic, severe PTSD showed that after 3 MDMA sessions, “67% of participants who received three MDMA-assisted therapy sessions no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis and 88% experienced a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms.”

Considerations and Participant Demographics

There are a few relevant notes about the study to keep in mind.

People often associate PTSD with military veterans due to their service and possible combat experience. Not only did the study include veterans with PTSD, but it also covered people suffering trauma from accidents, abuse, and sexual harm, most of whom endure developmental trauma. The majority of study participants were females assigned at birth who had experienced sexual abuse. A prior MDMA study enrolled only veterans and first responders with service-related PTSD, and results showed dramatic improvements in PTSD and depression symptoms.

The second Phase 3 MDMA trial (MAPP2) produced data that confirmed the findings of the first Phase 3 trial (MAPP1), which suggests that MDMA-assisted therapy can benefit a broader range of people who have PTSD. The participant population not only included those with varying degrees of severity but also individuals from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. It’s important to emphasize that this trial included participants with both moderate and severe PTSD, and about half of the participants were from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

It is crucial to include a diverse population in the trial because, due to disparities in trauma exposure, gender-diverse and transgender individuals, ethnoracial minorities, first responders, military personnel, veterans, and victims of chronic sexual abuse have a disproportionately higher risk of developing PTSD. This diversity means that the study provides a more comprehensive representation of the entire PTSD patient population.

Phase 3 Trial Results and Efficacy

MAPS reported the following summary of their second Phase 3 trial findings:

Participants in the MDMA-assisted therapy group experienced a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms versus participants receiving a placebo with therapy as measured by a change from baseline in the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (“CAPS-5”) total severity score (p < 0.001). The data also demonstrated that MDMA-assisted therapy significantly reduced clinician-rated functional impairment as measured by change from baseline in the modified Sheehan Disability Scale (“SDS”) (p = 0.0271). No serious adverse events were reported in either the MDMA group or the control group.

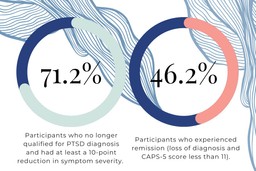

Six to eight weeks after the third MDMA session, 71.2% of participants in the MDMA treatment group had a loss of diagnosis (≥10-point reduction from baseline and no longer meeting PTSD diagnostic criteria), and 46.2% of participants met criteria for remission (defined as a loss of diagnosis and CAPS-5 total severity score of 11 or less).

The efficacy demonstrated in MDMA-assisted therapy clinical trials suggests a stark contrast to standard therapeutic methods (although there have not yet been head-to-head trials comparing MDMA to conventional treatments). Commonly prescribed medications (SSRIs, sleep aids, benzodiazepines, etc.) are often taken daily for years and, at times, forever. At the same time, MDMA is only administered a handful of times and produces far greater and longer-lasting benefits in many patients.

Many people fail to tolerate or respond to available PTSD medications and trauma-focused therapies, whereas the low dropout rate in MDMA studies suggests increased tolerability or patient preference for the treatment.

MDMA vs. Street Substances

Lastly, MDMA is not synonymous with or the same as “Molly” or “Ecstasy.” These types of street substances are often sold containing dangerous adulterants and may or may not contain MDMA. In the case of clinical trials, pure, laboratory-grade MDMA is used and thus far proves sufficiently low-risk for human consumption in limited frequency and moderate doses taken under medical supervision.

On that note, looking at the pharmacology of MDMA is a must.

What Does MDMA Do to My Brain?

MDMA and Neurotransmitter Release

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is a small organic compound known as a monoamine alkaloid, related chemically to amphetamine, that stimulates the brain to release neurotransmitters and hormones.

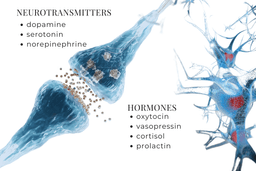

Neurotransmitters released: serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.

Hormones released: oxytocin, vasopressin, cortisol, and prolactin.

These neurochemicals dynamically interact to temporarily induce a unique brain state.

For a brief overview of the neurochemical process, please watch this video:

MDMA primarily works by releasing monoamine neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft by reversing the transporters that normally take transmitters back into the neuron. To a lesser extent, MDMA also acts as a neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitor.

The main monoamine neurotransmitter affected by MDMA is serotonin, although the dopamine and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) systems are also affected to a lesser degree. MDMA also has a weak affinity for some serotonin (5-HT) receptors; hence, some of its effects may be attributable to direct binding.

Thus, MDMA acts by releasing serotonin from storage vesicles and into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitters and their downstream receptor targets are responsible for the observed physiological and psychological effects of MDMA.

MDMA and Hormonal Effects

Secondary to the neurotransmitter release, MDMA is also known to elevate hormones – oxytocin, vasopressin, cortisol, and prolactin. MDMA has an intriguing relationship with oxytocin, albeit ambiguous. MDMA’s prosocial effects (friendliness, desire to bond, etc.) have been inconclusively linked to oxytocin. Oxytocin plays a key role in human mating and bonding. Most people know oxytocin as the “cuddle drug” or “cuddle hormone.”

Researchers have found that MDMA does increase oxytocin levels, although it’s unclear if oxytocin alone induces prosocial behaviors. The possible link between MDMA and oxytocin calls for more research. In the case that there is no direct link, then another interesting pharmacological effect produced by MDMA must be in play, likely through serotonin.

For an excellent, in-depth look at MDMA’s mechanism of action, metabolism, and neurochemical pathway, please watch this video:

Now that you have a basic understanding of MDMA’s chemical process in your brain let’s learn about MDMA’s effects: the good, the bad, and everything in between.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy Positive Effects

As noted above, MDMA stimulates the activity of happy brain chemicals and hormones like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, oxytocin, and vasopressin. In addition to this, MDMA also temporarily alters the physiology of the brain.

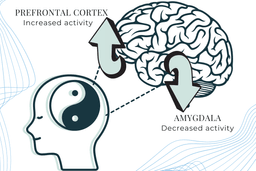

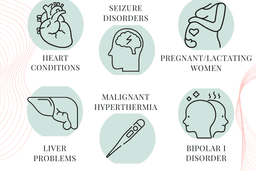

MDMA works in a yin-yang fashion, affecting the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.

MDMA and the Amygdala

Arguably, MDMA’s most crucial function in the context of PTSD treatment is that it reduces amygdala activity. Why?

As part of the limbic system, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the hypothalamus form the oldest part of the brain. The amygdala primarily manages aggression, anxiety, and fear. It also regulates emotion, mood, and behavior.

The amygdala regulating emotions makes more sense, knowing that the limbic system controls the fight, flight, or freeze response. This is where many PTSD symptoms stem from. Each time the trauma is recalled or activated, their limbic system gets triggered, and they replay the original trauma or associated emotions as if it’s happening all over again for the first time. Their limbic system can’t distinguish between the actual event and the stored memory of it.

The amygdala is the fear-processing center of the brain. So, people with PTSD often have a hyperactive amygdala.

MDMA and the Prefrontal Cortex

On the flip side of the yin-yang, MDMA stimulates prefrontal cortex activity. The prefrontal cortex is the higher processing center. So, MDMA activates neural pathways in the opposite direction than what typically presents in PTSD patients.

With PTSD, the brain has a hyperactive amygdala and a hypoactive prefrontal cortex. With MDMA, the brain has a hypoactive amygdala and a hyperactive prefrontal cortex. What’s the result of this neurological flip-flop?

MDMA targets the amygdala, the fear center, and dials it down. Meanwhile, MDMA “…increases connectivity between the amygdala and hippocampus.” The amygdala is the emotional arousal indicator. The hippocampus forms and retains memories. By acting on the amygdala, MDMA calms the fear response and appears to alter the way someone feels or perceives a trauma memory through the enhanced connection to the hippocampus.

This fear response impairment prevents an overwhelming emotional response, enabling the patient to remember and reflect upon the harmful trauma in a safe mental state with the help of therapists. This safe mental state creates a never-before-experienced space to process the trauma in a healthy, correct manner.

MDMA and Trauma Processing

Psychiatrist Dr. Michael Mithoefer describes MDMA’s unique ability to flip-flop focal centers of brain activity. In turn, MDMA helps the brain find the sweet spot for trauma processing, just the right balance between activation and safety. As Mithoefer says:

There’s also a concept in psychotherapy called the optimal arousal zone—the space between hypo- and hyper-arousal where the brain is alert but not threatened. It seems that MDMA gives people a period of time in a more optimal arousal zone, with less likelihood of being overwhelmed by fear. They’re also not dissociated or cut off from their emotions. They have a sense of connecting emotionally with what they’re talking about, but without being overwhelmed by the emotion.

A patient on MDMA enjoys a calm amygdala, reduced fear, and an active prefrontal cortex.

MDMA’s Effects on Mood and Perception

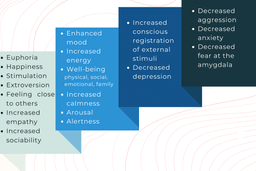

How does this brain state translate into everyday terms? MDMA effects may include euphoria, happiness, stimulation, extroversion, feeling close to others, increased empathy, increased sociability, enhanced mood, well-being (i.e., physical, social and family, emotional, functional), increased energy, increased calmness, relaxation, arousal, increased self-confidence, alertness, increased conscious registration of external stimuli, decreased depression, decreased aggression, decreased anxiety and fear, and mindfulness.

By no means is this an exhaustive list of MDMA effects, and how a person feels can vary depending on the setting where they take MDMA. For a complete list of MDMA effects, please look here. What’s the psychotherapeutic benefit, then?

MDMA’s Role in Psychotherapy

MDMA smooths communication and makes things look less threatening and fearful, nurturing people’s ability to experience each other in a more positive way. As Mithoefer notes, “It makes sense then that MDMA could make it easier to communicate if people weren’t as sensitive to interpreting someone else’s expression as being threatening.”

In doing so, MDMA paves the way for and accelerates bonding between therapists and a patient. Required bonding time is reduced, and a strong “therapeutic alliance” is formed. In all types of psychotherapy, this alliance is a known contributor to optimal outcomes.

By lowering defensiveness and boosting openness, MDMA becomes a psychotherapeutic performance enhancer by connecting the patient to their inner healing intelligence. Through non-drug integration sessions, the contents of the MDMA experience are examined under the guidance of the therapy team with the person’s personal goals in mind. In this way, the healing occurs over the weeks following the MDMA sessions as the insights and behavioral changes are implemented in one’s life.

MDMA as an Entactogen

In the end, remember MDMA is an empathogen or entactogen. An entactogen, which means “touching within or reaching inside.” Rather than having significant psychostimulant or hallucinogenic effects, MDMA powerfully promotes affiliative social behavior, has acute anxiolytic effects, and can lead to profound states of introspection and personal reflection. MDMA may facilitate a transcendent experience but more consistently induces greater access to emotions at a higher intensity. MDMA is not considered a classical psychedelic due to its unique pharmacology and its inability to duplicate consistent hallucinatory effects like LSD or psilocybin. However, many consider MDMA to be very “psychedelic”—especially regarding the term’s meaning of “mind-manifesting.” Users do report vivid imagery and memories under MDMA, but internal and external hallucinations are not as common and differ in quality from classical psychedelics.

Regardless of how beneficial this all sounds, MDMA still has some risks to be aware of, especially when taken in non-medical settings.

Negative Effects of MDMA

MDMA is a potent substance. Negative effects can occur during the MDMA experience and in the days and weeks following. Spacing MDMA-assisted therapy sessions at least 3 weeks apart is the procedure in clinical trials to reduce side effects and give ample time for integration.

When used in a controlled, clinical setting with medical screenings and specific exclusion criteria, MDMA has a good safety record. Since pure MDMA is used along with proper dosing, MDMA doesn’t pose as many risks compared to a recreational setting where the drug is often adulterated and environmental factors such as temperature aren’t regulated. Regardless of the setting, there are physiological commonalities, however.

Physiological Effects of MDMA

The physiological effects of MDMA include reduced or lack of appetite, restlessness, increased blood pressure, tachycardia, nystagmus (eye wobble, blurred vision), mydriasis (dilated pupils), panic attack, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, muscle tension, tremors, sweating, blurred vision, teeth grinding, jaw tightness and clenching, low to moderate potential for addiction or problematic use in non-medical sepoly-druggesearch includes poly-drug- users), dizziness, dry mouth, restlessness, feeling hot and cold, feeling of pins and needles, chest discomfort, chills, and feeling jittery.

One shared effect between a recreational and clinical setting is transient increased heart rate, body temperature (although the increase was not significant in MDMA phase 3 trials), and blood pressure. In clinical trials, vital sign increases are similar to moderate exercise and don’t typically pose issues for healthy individuals. But in recreational settings (e.g., festivals), Ecstasy users are at greater risk for adverse effects if they become dehydrated, take multiple substances, or get overheated from high ambient temperatures or prolonged dancing.

This distinction between potential risks in medical vs. non-medical settings is important because serious cardiac events such as tachycardia (fast heart rate) and arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat), hyperthermia (elevated temperature), hyponatremia (low salt) have nearly all occurred in non-clinical contexts under high doses and in individuals that had prior medical conditions or were taking medications that interact with known or unknown poly-drug-use.

MDMA’s Acute Effects and Safety Considerations

In light of this, clinical use selects out people with serious medical issues, particularly cardiovascular diseases, due to MDMA’s ability to increase blood pressure and heart rate.

One study acknowledges the same and goes further, stating possible acute effects. This MDMA-assisted psychotherapy study for anxiety in patients with a life-threatening illness reported the following MDMA side effects:

After MDMA administration, the MDMA group’s vital signs increased to expected levels, with only body temperature rising higher than the placebo group. The MDMA group also reported more adverse reactions during the experimental sessions, including jaw clenching/tight jaw, thirst, dry mouth, and perspiration. Reactions were short in duration and mostly subsided by the end of an experimental session or during the week following. Psychiatric adverse events were infrequent, and MDMA was not associated with serious suicidal ideation or behavior. Overall, the safety profile for MDMA in this controlled clinical setting indicated that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy was a safe treatment in this relatively small sample where the benefits outweighed the cost of mild and short-term reactions.

Post-Session Effects and Tolerability

The study authors discuss the effects of MDMA in the days and first week following a session. The common effects 7 days following an MDMA session include insomnia, low mood, fatigue, and needing more sleep, while symptoms decreased with each day.

Mithoefer concurs with this finding, saying, “People usually feel physically tired afterward, as it takes a bit of a toll on the body. Most people need a day or so to recuperate and get their energy back. It’s not the kind of thing you’d want to take all the time.”

When patients are screened for specific psychological and physiological health criteria, MDMA is well-tolerated. Moreover, with body temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate increases similar to moderate exercise, and it has low potential for abuse in medically supervised administrations, so far, MDMA appears to be safe for use in clinical settings.

Potentially Significant Drug-Drug Interactions with MDMA

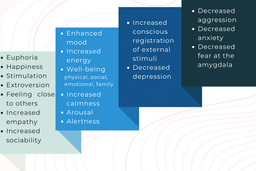

Some medications and drugs are not recommended for use with MDMA. The main drugs and substances that can be potentially harmful and increase side effects in conjunction with MDMA are serotonergic drugs like SSRIs (may cause serotonin syndrome; can be fatal), MAO inhibitors (prescribed as antidepressants can cause serotonin syndrome; can be fatal), drugs metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP2D6, drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 such as antiretroviral medications like ritonavir, alcohol, and other stimulants.

This is not a comprehensive list of medications that may have drug interaction with MDMA. Careful review and clinical consideration need to be performed by a healthcare provider to assess if MDMA can be given with other medications.

Conditions with Greater Risks in MDMA-Assisted Therapy

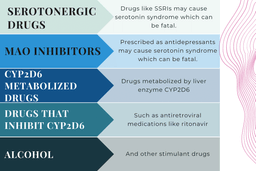

In addition to medications that increase risks, some health conditions are associated with increased risks and side effects if MDMA is taken. Because MDMA increases heart rate and blood pressure, heart conditions can heighten the likelihood of life-threatening adverse effects, such as heart attacks. These pre-existing health conditions are not recommended for MDMA use and warrant extreme caution.

MDMA has undergone limited testing in clinical trials. Therefore, to maximize safety, participation has been limited to physically healthy individuals and those with stable medical conditions that don’t pose a high risk for complications due to MDMA.

Participants with a history of coronary artery occlusion and cardiovascular conditions, including torsade de pointes, heart failure, hypokalemia, prolongation of QT/QTc interval, or family history of Long QT Syndrome may be at greater risk for negative effects after ingesting MDMA if they have a history.

Other Conditions That May Pose Risks

MDMA is broken down in the liver. If liver problems are pre-existing, such as hepatitis, damage to the liver, or other adverse effects may occur after MDMA ingestion. There is no evidence of liver damage by MDMA alone in healthy individuals, and studies in patients with liver failure have not been performed.

Seizures can be more likely to occur while on MDMA in people with a prior history of seizures. Seizure disorders have not been tested with MDMA, and therefore, it is not recommended for patients with this history to participate in clinical trials.

People with malignant hyperthermia, central core disease, or other susceptibility to heatstroke should be extremely careful if they take MDMA. Body temperature spikes and severe muscle contractions occur when a person is administered general anesthesia that has malignant hyperthermia. After MDMA, people with this disease could potentially experience heat stroke or other severe symptoms.

Individuals with prior occurrence of hyponatremia or hyperthermia may be more likely to experience negative effects with MDMA.

Pregnant and lactating women should not take MDMA as this treatment modality has not been studied in this population.

Psychosis could be introduced by MDMA in those with psychotic disorders or mania (with or without psychosis) in those with Bipolar I Disorder. Insufficient research exists in these populations to describe the outcomes of MDMA ingestion, so caution is warranted.

Insufficient research also exists in regards to MDMA interactions with pharmaceuticals and drugs of abuse. More studies, cases, and data are called for.

MDMA History and Law

MDMA was first synthesized in Germany around 1912 by chemists at the pharmaceutical company Merck. Later, in 1914, Merck patented MDMA, guessing it could have pharmaceutical value. MDMA was originally discovered by Merck when it was in search of a drug to stop bleeding. MDMA was patented as an intermediate in the synthesis of blood-regulating compounds Merck was working on. At the time, its psychoactive properties were not recognized.

Several decades passed until further drug development was undertaken. Fast forward to the 1970s.

Even though MDMA was not an FDA-approved medication, it was still legal. MDMA “…first reached widespread popularity as a legal alternative after the much sought-after recreational drug 3,4-methylenedioxy-amphetamine (MDA) was made illegal in 1970.”

Then, from 1977 to 1985, while MDMA was still legal and unregulated, the substance spread through a few dozen psychotherapists “…because of its benign, feeling-enhancing, and non hallucinatory properties…” It was used in couples’ therapy to open lines of communication and facilitate bonding, but it was never researched in formal settings.

When the 1980s came around, MDMA became known more as a party drug.

Then the inevitable arrived, “In 1985, the DEA declared an emergency ban on MDMA, placing it on the list of Schedule I drugs, defined as substances with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” The DEA later permanently placed it on Schedule I in 1988.

For an excellent and detailed account of the origins of MDMA in the USUand psychotherapy, please read this timeline.

Psychotherapeutic Applications for MDMA

MDMA-assisted therapy shows great promise in treating a variety of disorders and trauma types. The following list is some of the conditions MDMA is being investigated for conditions comorbid with trauma (i.e., substance use disorder, alcoholism), post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and distress related to a life-threatening illness, social anxiety in autistic adults, anorexia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.

To learn more about the psychotherapeutic applications of MDMA, please take a look at this list of highlighted literature and news below:

Clinical Trial Publications of Therapeutic Use

Here’s a sampling of the most impactful findings from MDMA-assisted psychotherapy clinical trials.

- MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study (MAPP1)

- MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (MAPP2)

Clinical Trial Records

For a full MDMA trial list and searchable map, go to our How to Join a Psychedelic Clinical Trial page.

MAPS MDMA Manual and Investigator’s Brochure

For an intensive and detailed, step-by-step examination of the MDMA-assisted psychotherapy process, please refer to the MDMA Treatment Manual.

The MDMA Investigator’s Brochure is a regulatory document informing investigators of all safety and efficacy findings. The document is updated annually.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy Testimonials from Patients

Some clinical trial participants have volunteered to go public with their journey and talk about how MDMA-assisted psychotherapy helped them heal. The best way to learn about the potential of MDMA as medicine is the people who’ve used it to heal.

Two of the earlier participants in the MDMA clinical trials were Rachel Hope and Tony Macie. Rachel endured a childhood filled with neglect and abuse, only to witness her husband die years later. Macie is a retired Sergeant in the US Army, completing a 15-month tour in Iraq from 2006-2007 and witnessing fellow soldiers die. Watch MAPS document Rachel’s and Tony’s journeys here:

In 2015, Rachel hosted this popular Reddit thread. Rachel even made it on TV with the opportunity to talk about her amazing healing experience.

If you’re interested in learning more in-depth about Rachel, watch this half-hour podcast, Mother of Four Cures PTSD With MDMA.

Tony also took to Reddit to host an “Ask Me Anything” back in 2014. “I’m a veteran who overcame treatment-resistant PTSD after participating in a clinical study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. My name is Tony Macie— Ask me anything!”

Tony’s and Rachel’s stories helped support the clarion call for alternatives to the current mental health model and SSRIs. Their message went far and wide.

Other Voices in the MDMA Therapy Movement

Tony’s journey went so well that he dropped out after only one session. He became one of the most prominent voices advocating for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. He’s featured here again in this well-done Vice News piece about MDMA curing PTSD.

Along with Tony, Vice News documents the story of their very own reporter- Ben Anderson. Anderson suffered trauma on assignment and had PTSD for years following until he sought out MDMA treatment.

Ben’s own PTSD journey connects him with other veterans besides Macie, like Jonathan Lubecky.

Lubecky has also become a prominent voice advocating for MDMA therapy. Lubecky is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran after serving in Iraq from 2005-2006. He was knocked unconscious in a mortar attack and suffered a traumatic brain injury, and PTSD followed.

After five suicide attempts, he had nothing to lose. Lubecky figured, “was going to die anyway, that I might as well try ecstasy. And then it worked.” The Marine Corps vet has gained notoriety for his upbeat quote about MDMA therapy, which he also acknowledges as hard work:

It’s like doing therapy while being hugged by everyone who loves you in a bathtub full of puppies licking your face.

Watch it here.

Finally, there’s Nick Watchorn. Nick was a first responder at the Port Arthur massacre in Port Arthur, Tasmania. The 1996 mass shooting left 35 people dead and 23 wounded. He tells his story of struggling to cope.

Psychotherapy Testimonials from Therapists

So, what do therapists have to say? The picture wouldn’t be complete without hearing from a therapist’s perspective, especially regarding a not-yet-legal treatment. We know three therapists who provide valuable insight into this novel field.

They are Evan Sola, Genesee Herzberg, and Sylver Quevedo.

Evan Sola, PsyD

Evan is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in San Francisco and Berkeley and a psychedelic researcher in FDA clinical trials for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD at UCSF and Polaris Insight Center. He has a background in trauma-informed psychodynamic and Jungian psychotherapy and uses dreams to explore attitudes unconscious to the waking self. He provides psychedelic integration for those exploring non-ordinary states, spiritual emergencies, grief, and overwhelming life adjustments and offers ketamine-assisted therapy for depression and acute suicidality at Sage Integrative Health.

Genesee Herzberg, PsyD

Genesee received her doctorate in Clinical Psychology from the California Institute of Integral Studies, where she wrote her dissertation on the phenomenology and sequelae of MDMA-assisted therapy. She trained in MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and in ketamine-assisted therapy with the KRIYA Institute. Dr. Herzberg is co-founder and Clinical Director of Sage Integrative Health, a holistic health and ketamine clinic in Berkeley, CA, that offers psychedelic-assisted therapies as they become legal from a holistic, trauma-informed, and relational perspective. Dr. Herzberg offers individual and couple therapy, ketamine-assisted therapy, and psychedelic integration with a specialization in developmental trauma. Her approach is depth-oriented, relational, somatic, and mindfulness-based, with a social justice lens. Dr. Herzberg also works as a co-investigator and therapist for MAPS’ MDMA for PTSD research trials.

Sylver Quevedo, MD

Sylver has been in continuous practice of medicine for 40 years and practices nephrology, family, internal, and integrative medicine. He is the Co-Founder and Medical Director at Polaris Insight Center and serves as an Assistant Professor at Stanford and the University of California, San Francisco. He has played pivotal roles in several global health projects, including the planning and development of a medical and nursing school in Africa. Dr. Quevedo is trained in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy and has worked as a therapist on MDMA phase 2 and phase 3 trials.

Learn More

Get familiar with Evan, Genesee, and Sylver in this video.

This video is taken from our Foundations in MDMA Safety, Therapeutic Applications & Research course. The course is your complete guide to exploring MDMA-assisted therapy and learning about the latest clinical protocols and trial findings. Differing hypotheses regarding the effects of MDMA on the brain are also covered.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy Training Opportunities

Ready to get started? We’re offering a free guidebook and online courses.

Click through here, give us your email, and we’ll send you a FREE PDF of The Little Book of Psychedelic Substances. We want to be good guides and teachers, so we offer free psychedelic courses and education.

When you are ready to go deeper into the science and therapeutic approaches, enroll in our evidence-based, self-paced course on MDMA (CE/CME credits available)! This course is perfect for health professionals, neuroscience and psychology students, and anyone who wants in-depth knowledge of psychedelics.

This substance guide was initially published on August 2, 2021, and updated regularly to reflect the latest information on MDMA research, therapy, and treatments.